The Cornish Rebel

Cornwall, 1801.

In the wake of her mother’s death, Pandora Woodville has finally escaped her domineering father and returned to Falmouth. Bright with the dream of working at her Aunt Harriet’s school for young women, Pandora is shocked to learn the school is facing imminent closure after a series of sinister events has threatened its reputation.

Acclaimed chemist Benedict Aubyn has also recently returned to Cornwall, to take up a new role as Turnpike Trust Surveyor. Pandora’s arrival has been a strange one, so she is grateful when he shows her kindness. As news of the school’s ruin spreads around town, everyone seems to be after her aunt’s estate. Now, Pandora and Aunt Harriet must do everything in their power to save the school, or risk losing everything.

However, Pandora has another problem. She’s falling for Benedict. But can she trust him, or is he simply looking after his own interests?

Waterstones

Atlantic Books

Barnes and Noble

Kobo

Hive

Rakuten Kobo

Blackwell’s

Amazon

WHSmith

Australia : New Zealand: US

Member of the Historical Writers Association and the Romantic Novelist Association

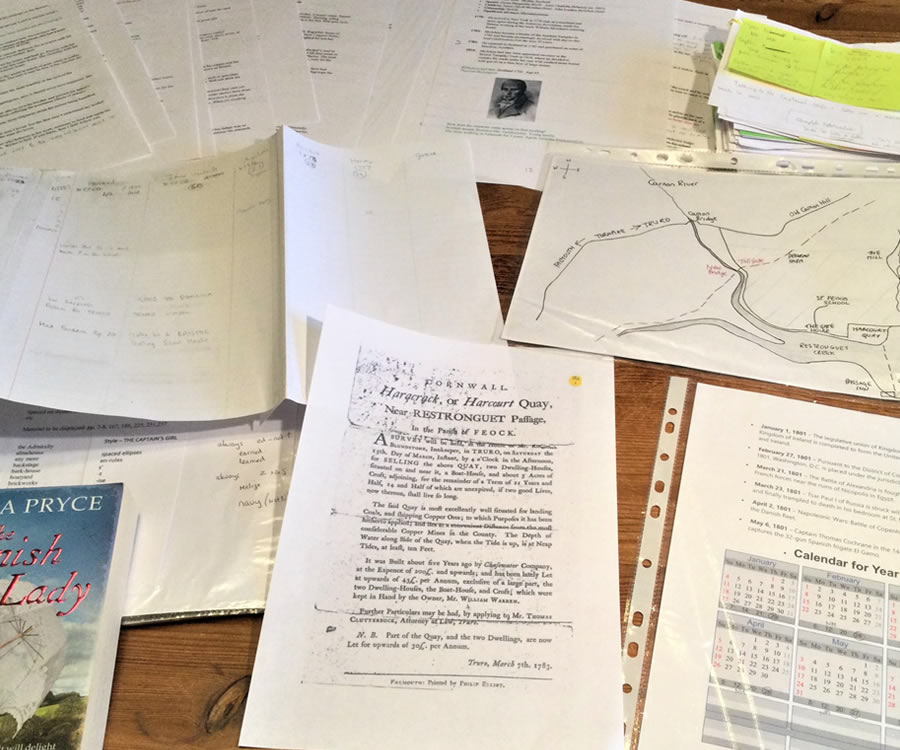

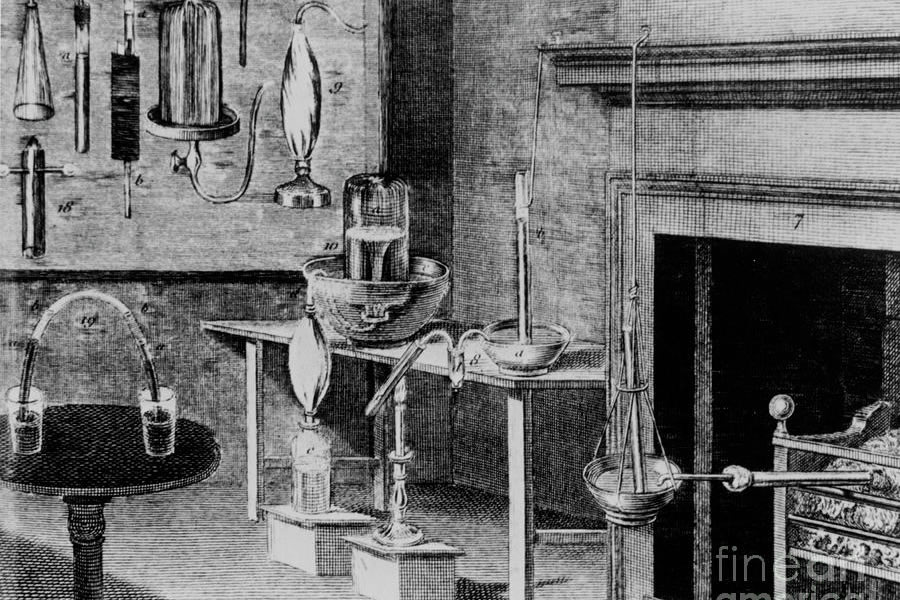

In 1801, the old turnpike road from Truro to Falmouth was getting increasing overcrowded, especially in Carnon Hill where it was very steep. The old pack horse bridge, Carnon Bridge, was frequently congested with long queues stretching in both directions. Built in 1754 it was the first and largest turnpike road in Cornwall, used extensively by the Falmouth Packet Company as part of the ‘packet’ route taking post from London to the British Empire, but by 1801 the stretch of road through Perranarworthal was proving unfit for purpose. Britain was at war, Falmouth a busy naval port, and commerce in the area was booming. Tin and copper needed to be exported by sea and the naval ships needed provisions.

I came across the old map, entitled Plan of the Present and Proposed Roads from Truro to Falmouth in Kresen Kernow in Redruth which showed the proposed new Turnpike route and my story started to take shape. Whose land was it going to cut across? Would they welcome it?

Painted by Sally Atkins www.thesunnycupboard.co.uk

“ Crossing the room Benedict Aubyn picked up his bag and drew out Aunt Hetty’s chair. Doing the same for me, he finally seated Grace and sat between us. The brass clasps snapped open and Aunt Hetty drew a deep breath. ‘A map, Mr Aubyn? That can only mean you’re planning a new road.’

He looked slightly shaken and I tried to hide my smile. ‘If I may just show you?’ It was not the voice he had used to negotiate his ten per cent commission, more the voice of a pupil who feared he had got his Latin wrong. Unrolling the map, he glanced at Grace. Smiling, she leaned towards him and offered to hold down the edges. Aunt Hetty remained impassive, though I sensed her breathing quicken. ‘I’d like … that is… I’ve come to ask if I may survey your land?’

‘Do you need my permission, Mr Aubyn?’ Not quite the sharp rebuke I knew to my cost, but certainly a tone he could not fail to understand.

He swallowed, reaching for a printed page and held it to the candlelight. ‘Legally, the Turnpike Act governing the Truro to Falmouth Turnpike Trust grants the Trust power to access any land for the purpose of widening the road … and for obtaining stone or gravel to maintain the road. And for the purchase of land. That is … to buy land to widen an existing road … and … or … for the express purpose of building a new road.’

‘So the answer is, no, you don’t.’

He swallowed again, a slight heightening of his colour. ‘Not as such, but I’d prefer it if you gave me your permission.’

I held my breath. ‘Then you have it, Mr Aubyn. I appreciate your candour.’

He looked almost believable, not a wolf in sheep’s clothing at all. His clever use of solemnity was a winning ploy, his quiet praise of the portraits and minerals highly effective. Neither overly friendly, nor condescending, he hardly sounded enthusiastic. Cleverer still, he had not tried to charm or cajole her but had appeared to want to please her. A polished performance, considering how much money was at stake.”

Page 65.

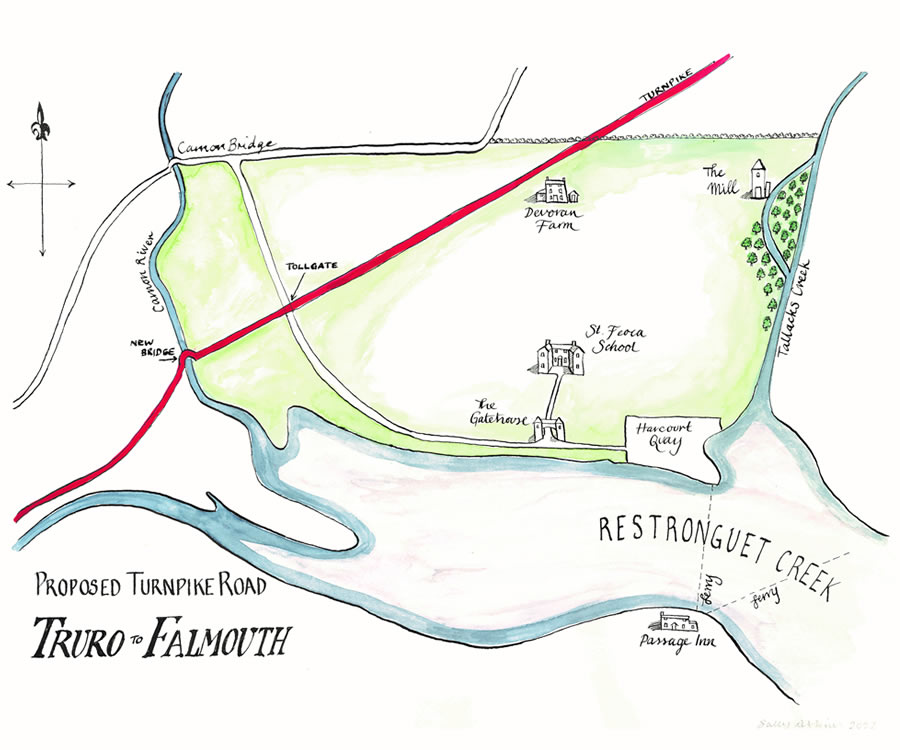

“The chanting quietened to a murmur and the magistrate on the platform tried again, this time with a megaphone. Holding up a piece of paper, his voice was educated, refined, edged with fear. ‘I’ve received your complaints. I have names … and the incidences of forestalling you claim to have occurred.’

A voice rang across the crowd. ‘Selling corn before it reaches the market is against the law. Storing corn to profit at a later date is against the law. We don’t claim anything, sir. We’re telling you the facts. Money’s being made … people profiting while our children gather nettles an’ fight dogs for potato peelings. Loaves at one shilling and tuppence – who can pay that? We’re starving while the famers prosper.’

Crushed on both sides, I tried to push my way through the shouts. A man’s elbow caught my cheek and I winced in pain. A sudden surge forced me forward and a woman grabbed my arm. ‘Take care, my love. Keep on yer feet. Stand steady, ye looked washout out.’

Once again, the voice boomed through the megaphone. ‘Shortages are to blame. I don’t need to tell you that. No corn is being stored. There’s just no corn. I can find no adulteration of the flour. No chalk or grit’s been added. The bakers aren’t poisoning you. They’re honest men with livings to make.’ The rumble was growing again, the murmurs getting louder and a note of steel entered his voice. ‘Go home. Go home. I have your list of grievances. I will see to it. I will investigate your claims. I will –’

The sound of crashing glass stopped him. To my right, a deafening shout. The crowd surged forward, and I felt myself almost lifted from my feet. A loud whistle, shouts, a woman was screaming. Red uniforms were forcing their way towards us. ‘There … that one. Those over there. That woman with the placard. Get that man … that one. Round them up.’

Like a wave, the crowd swept forward. I could hear punching, scuffling, angry grunts; a fight broke out, a man with blood dripping from his nose. I tried to break free but a woman beside me gripped my arm. ‘Stay upright, my love. Don’t stumble or ye’ll be trampled.’ In her other hand she raised her banner, waving it defiantly.”

Page 156.

“ The clouds had lessened, a brightness to the sky. Ships were sailing up the river, the outline of Pendennis Castle just visible. ‘Did you come to watch the birds? Tallacks Creek is particularly peaceful, don’t you think?’

We stood staring across the silent water. ‘Benedict – I’m glad we have this chance to talk. Only, yesterday, I told you things I should never have told you. Not to stranger … not to anyone.’

The warmth in his eyes was disconcerting. ‘You were very shocked. What you had just learnt was very distressing. It’s natural you needed to speak of it. I only hope I was able to help.’

A blush made my eyes water. ‘What I said was very intimate. I’d like you never to speak of it to anyone.’

‘You’ve no reason to ask that. You already have my word.’ His words were sharp, accompanied by a frown.

‘Thank you. And I must thank you for your advice. You were right. My aunt needed to know. So much better to tell the truth.’ My throat felt tight, I was in grave danger of crying. The horrific dolls had kept me awake, the thought of such evil sending shivers down my back.

He pointed across the water. ‘Look, an egret … and a heron. That’s a curlew.’

Biting my lip, I stared across to Falmouth. A fisherman was throwing out his net, the surface rippling, gulls dipping and disappearing beneath the water. The air smelled of distant woodsmoke and I fought my growing emptiness. If I knew anything, it was to keep men at arm’s length. ‘Is that yawl dredging for oysters?’

‘Yes, it is. Pandora, you’ve made your dress very dirty on my account – your boots are caked in mud. May I help you clean them?’

‘No, I was muddy before. This is my old gown and my working boots. I was gardening when I decided to go for a walk.’

He looked away. ‘You’re a keen gardener?’

‘I know nothing about gardens but I’m going to restore Grandfather’s garden. Apparently he kept saying, But we must cultivate our garden; and so I will – for him. I remember him wearing a leather apron and digging the beds.’ I was talking too fast, gabbling my words. Trying to sound buoyant.

He turned and I avoided his eyes. ‘That’s from Candide – it’s how the book ends. Have you read Voltaire’s Candide?’ I shook my head. ‘You might enjoy it. It’s a satire. A group of characters set off to find Eldorado because they hear the streets are lined with gold. They pit their wits against every extreme and in the end decide all the riches they could possibly want can be found in a garden. No one needs to circumnavigate the world to find riches. They just need to cultivate a garden.’ He coughed. ‘I’m sorry. That was very insensitive of me.’ ”

Page 189.

Who is Aunt Hetty based on?

I came across Miss Mitchell, the headmistress of a girls’ school in Truro, in Viv Acton’s comprehensive book A History of Truro, Volume 1, and incorporated her into my novel The Cornish Lady little knowing that three novels later she would become one of my favourite characters. In retrospect, perhaps I should have changed her name as my portrayal of her is entirely fictional. In her book, Viv Acton tells us that Miss Mitchell was a ‘sensible and well-informed lady.’ The daughter of the Vicar of Veryan, Miss Mitchell started her boarding school for girls in the middle of the eighteenth century in the Great House, moved it to the large red brick house, which is now City Hall, and then to Tregolls on the outskirts of Truro. It appears, however, that her school was not hugely successful. According to the Cornish clergyman, poet, and historian, Richard Polwhele, she ‘aimed too high for the country’ as most people expected very little of ladies of high society – simply to be gracious hostesses with few intellectual accomplishments. An oft quoted lament.

St Feoca School for Young Ladies is imagined, but after I had written the description I came across a photograph of a school called Polwhele House which is almost exactly how I describe St Feoca. It was one of those spine tingling moments which often happen during research. Polwhele House has the same history and the same tower but it is nearer Truro. This photo is taken from the school’s website.

Who is Benedict Aubyn based on?

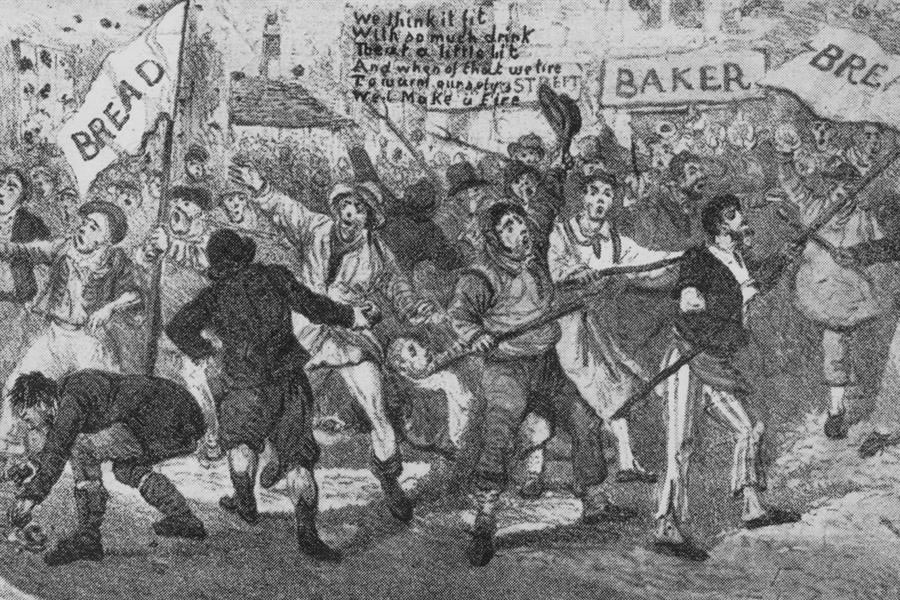

Tin and copper mining naturally sparked an interest in minerals and mineral collecting. Many new minerals were discovered in Cornwall including manachante, sometimes called menaccanite. In 1790 William Gregor discovered ilmenite, an iron titanium oxide, in Gillan Creek and went on to find a new element, titanium, which he called menachine. One well known collector was Philip Rashleigh whose mineral collection is housed in the Royal Cornwall Museum in Truro.

Alongside collecting minerals came a burgeoning interest in the new science of chemistry. Men of science began analysing and investigating the properties of each new mineral and Dr Richard Edwards AB Oxon(1801) AM(1801) MB(1802) MD(1802) FRCP(1803), was one of these new scientists. An accomplished chemist and lecturer in science at St. Bartholomew’s hospital, he returned to his native Falmouth in 1808 and is the inspiration behind Benedict Aubyn.

The area around Restronguet Creek, Bissoe and the Carnon Valley was home to the early arsenic industry. Arsenic is found in the mined ores of tin and copper and causes the metals to be poor quality so it is important to remove it. In 1801 this was achieved by roasting the ore in a furnace called a calciner. The resulting arsenic gas was carried away in fumes breathed in by the furnace workers and the miners around the furnace. Arsenic poisoning was an occupational hazard but it also spread to cattle and livestock as the white powder in the waste ore caused considerable contamination to the surrounding land.

A system was needed to capture the arsenic gas and control the white oxide dust which was doing so much damage and Dr Richard Edwards of Falmouth did just that. In 1812, he discovered a process to condense and collect the white arsenious oxide dust, and thus managed to contain the arsenic and stop it contaminating both the people and the land.

He set up works at Perranwell Foundry to extract refined arsenic from mine waste and render it in to a solid state. He did this by using a Bruton Calciner whose long labyrinths ‘captured’ the white arsenic in crystal form. One such Bruton Calciner can be found in Wheal Busy, Chacewater. The process soon got financial backing, not least once they discovered arsenic had certain useful properties and a commercial value of its own.

A Chemist and an Assistant in a Laboratory by L. R. from History of Science Museum

Priestley’s Apparatus For Investigating Gases. Priestley’s apparatus. Engraving of the laboratory of the English gas chemist Joseph Priestley (1733- 1804), showing various pieces of experimental apparatus. Science Photo Library

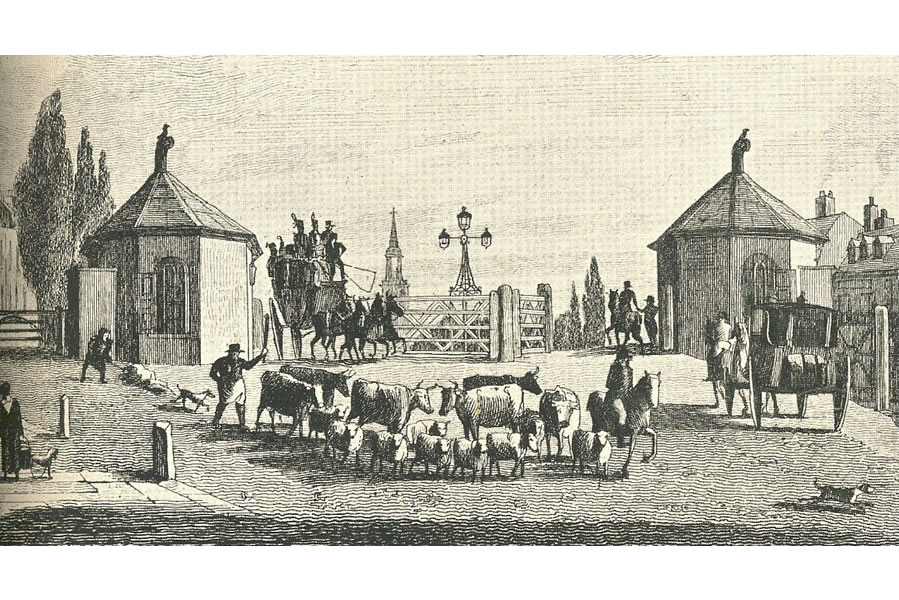

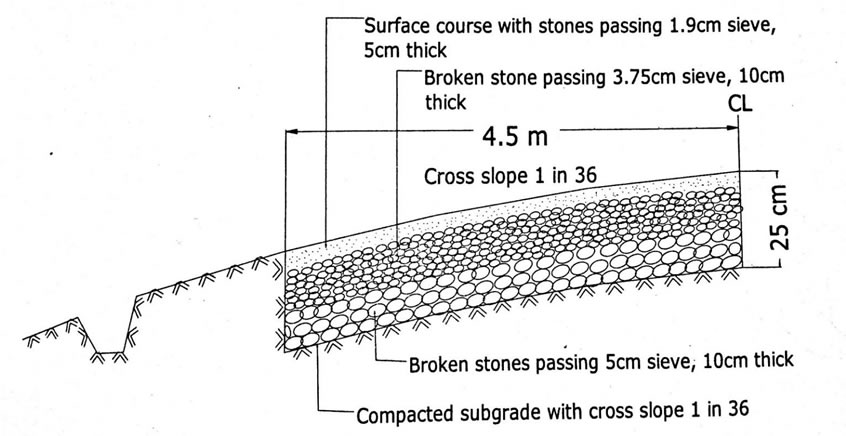

When I discovered that John Loudon McAdam was in Falmouth in 1801, I knew I had to incorporate him in my book. John McAdam left Falmouth just after 1801 to join the the Bristol Turnpike Trust. At the time, his views on road building were considered radical, believing as he did that roads did not need to have heavy stone foundations but thin layers of smaller stones laid over a subsoil base. Even more radical was his opinion that once laid, each layer should be left to be compacted by the weight of the vehicles before the next layer was added. His ‘macadamized’ roads as they became known enabled horses to pull three times the load without the danger of causing ruts. Wagons and coaches were also able to carry heavier loads and travel at far greater speeds.

Taken from Macadam Road: 4 types dreamcivil.com

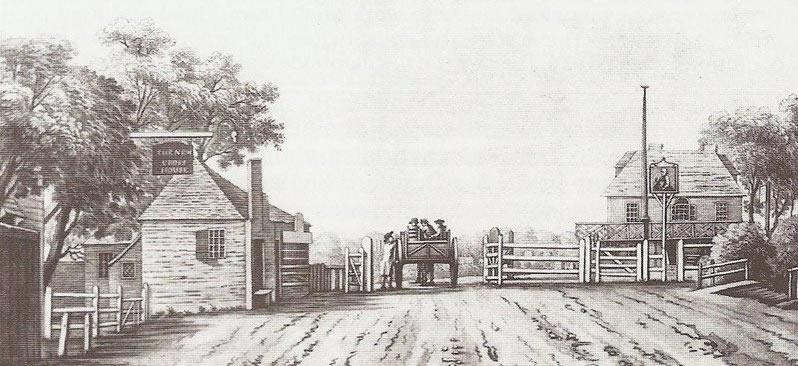

Turnpike roads

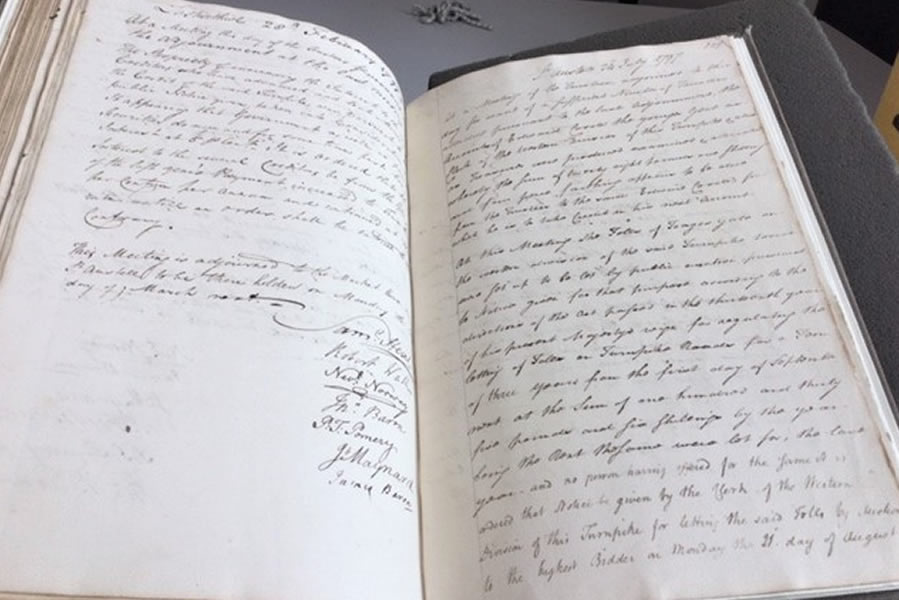

Minutes of a St Austell Turnpike Trust meeting 1797. Copyright Kresen Kernow. Not to be reproduced.

Each Turnpike Trust was established separately through an act of parliament which granted the trust the power to raise funds to pay for the road by seeking investors who could expect a healthy return. The Trust levied charges, through tolls, and had to keep the roads in good order. By the end of the eighteenth century however, it was becoming clear that many of the Turnpike Trusts were fraudulently set up with huge profits going straight to the Trust directors.

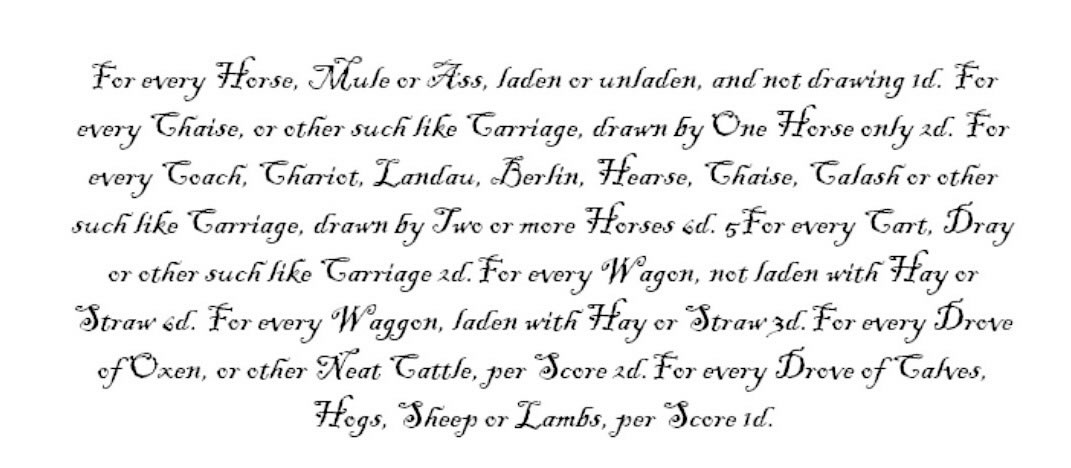

In my book, I mention the auction of tolls. I found this discovery very interesting. An auction would be held for everyone interested in becoming the tollgate keeper. Each hopeful applicant would put in a private bid of what they would pay the Turnpike Trust per year and the highest bidder would be given the job, and possession of the tollhouse, and would be in charge of collecting every toll. If the sum of the tolls came to less than the gatekeeper had pledged he would bear the brunt of the loss, but any money received over his bid would be his to keep. Apparently, at the Falmouth Gate the toll keeper’s annual income could exceed four hundred and twenty pounds after deducting rent and expenses. A very good income for 1801.

But where to site the new, improved road? This was always the question. Directors of the trusts were often local land owners or men of commerce who sought to bring a decent road to the end of their driveway or their foundries and wharfs. Many, however, were determined to keep all traffic away from sight of their fine houses.

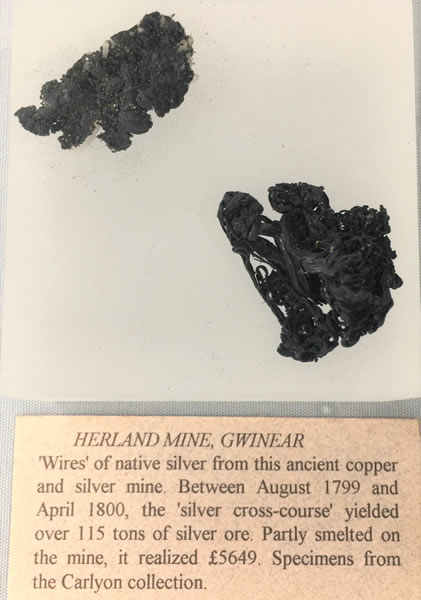

Silver in Cornwall

In the thirteenth century silver was mined in Cornwall and enough was raised, reportedly, to enable Edward I and Edward III to pay off their war debts. However, the mines closed until the 1500s when they were reopened, but only a small amount of silver was found. In the late 1700s, silver was discovered in Huel Mexico which was then re-opened. Next, silver was discovered at Herland Copper Mine, Gwinear, in 1793 which was, at first, fairly successful.

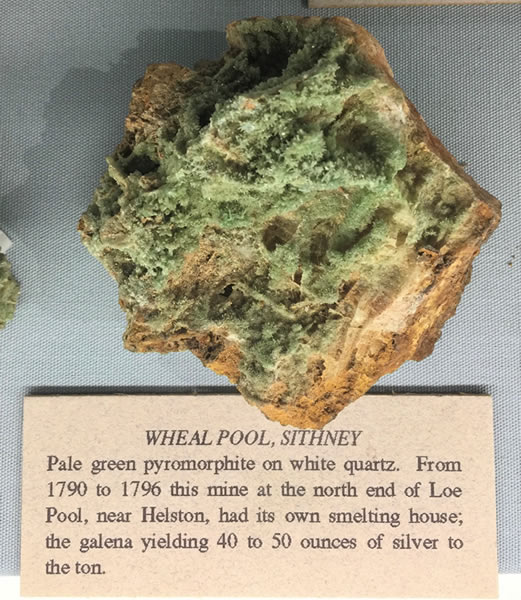

It was while I was studying the minerals in the Royal Cornwall Museum and came across the following two exhibits that my story began to develop.

Herland Mine, Gwinear. ‘Wires’ of native silver from this ancient copper and silver mine. Between 1799 and April 1800, the ‘silvercross-course’ yielded over 115 tons of silver ore. Partly smelted on the mine, it realized £5649. Specimens from the Carlyon collection.

Wheal Pool, Sithney. Pale green pyromorphite on white quartz. From1790 to 1796 this mine in the north end of Loe Pool, near Helston, had its own smelting house; the galena yielding 40 to 50 ounces of silver to the ton.

Animalcules.

Harriet Mitchell owns several microscopes, one no doubt similar to this beautiful microscope which is part of the collection belonging to the Royal Microscopical Society. Gerald Turner describes it in The Great Age of the Microscope as a Cuff-style microscope that may well have been made by famous Ausburg scientific instrument maker Georg Brander in the late eighteenth century.

Animalcule, a word derived from ‘little animal’, is the name given to microscopic organisms at the time of my book – what we now know as bacteria, protozoans, and very small animals. The word was invented by the 17th-century Dutch scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek to refer to the microorganisms he observed in rainwater. Antonie Philips van Leeuwenhoek (1632 –1723) was a mainly self-taught Dutch microbiologist in the Golden Age of Dutch science and technology and is commonly known as “the Father of Microbiology“.

Paints and painted oyster shells.

I was lucky enough to come across this photo of two eighteenth century painted oyster shells, recently sold by the antiques company, Xupes, for £650. They were able to authenticate the shells and dated them from the early 1800’s. Interestingly, you can’t see any red on the union flag on the first ship. Had the red been visible, and had it just been vertical and horizontal, we could have dated it before the Act of Union with Ireland in 1801. After that act, the cross of St Patrick was added and we get the red cross.

At the time of my book an important purveyor of paints was a London firm called Reeves and Woodyer who supplied paints from their shop in Holborn. As well as fine lead pencils and charcoals, they sold solid cakes of water colours either individually or in fancy box sets of yew, mahogany, or satin wood. Reeves is credited with having invented the soluble watercolour.

Or if, like my heroine Pandora, you preferred softer paints that lasted longer, you could buy the special Ackermann paints which were mixed with honey and gum Arabic.

Ackermann’s Superfine Water Colours were made and sold from Rudolph Ackermann’s shop, The Repository of Arts at 101 Strand in London. Many print and booksellers also stocked his paints, together with suitable paper for painting watercolours.

Certainly they would have been available in Falmouth, and not just for well-bred ladies. Many sailors bought paints – indeed, there used to be a saying that there was more painting done on board ship than polishing!

Photo credit: naturalpigments.com

Mourning clothes

I can’t resist including these beautiful prints of ladies in mourning, as might have been worn by Harriet Mitchell and Pandora. The first two are dated 1797, the third 1805.

From The Ladies’ Magazine September 1805. Copyright Amy de la Haye

Fire Pumps

This is the four man water pump on which I based Lord Carew’s fire pump. It’s thought to have been made by Samuel Phillips of New Surrey Street, Blackfriars, London in the second half of the 18th century. He started making engines as early as 1760. In 1797 he became Philips and Hopwood. According to the museum’s website, Josiah Wedgwood of pottery fame ordered one in 1781 and paid just under £60 for it which would be about £13,150 today.

The smaller pumps were worked by four men but as many as twelve men were needed for the larger versions. The men raised and lowered long handles called ‘brakes’ on either side of the chassis and the water was tipped into the tank by men rushing back and forward with buckets. Some later engines came with a suction fitting which drew water directly from a nearby pond or river.

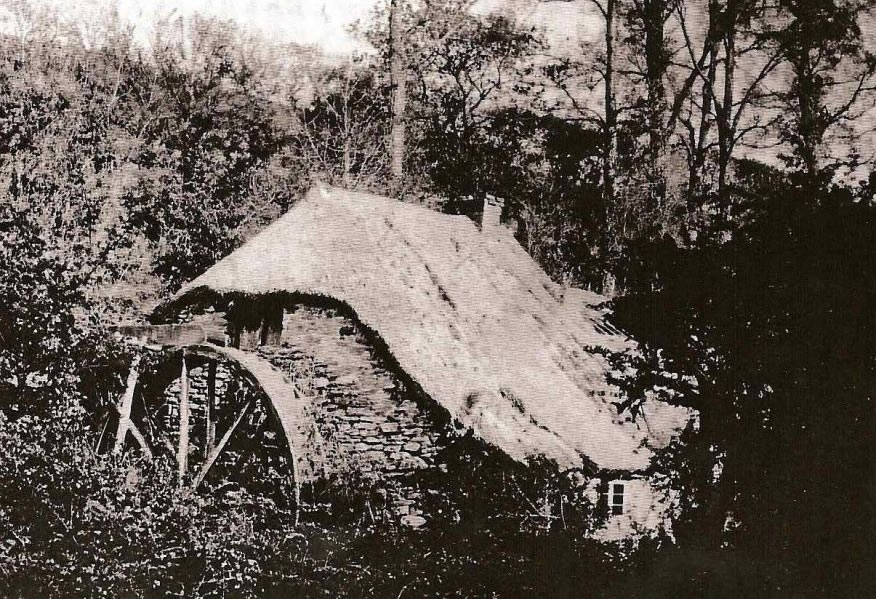

The Corn Mill in Tallacks Creek

The mill in my story is based on Penpoll Corn Mill in Restronguet Creek, as photographed here by Bob Acton. For more photographs of the area, please visit RestronguetCreekSociety.org.

Tregenna Hall

Pengreep Estate. Credit: Jonathan Cunliffe

By complete coincidence I had just reached the stage in my book where I was about to describe Sir Anthony’s house. It was to be a large house and I had already described the lake full of brown trout, the walled kitchen garden, and the sunken terraces. I usually have a house in mind when I write but I didn’t for Sir Anthony Ferris. I hate making things up, so imagine my delight when out of the blue I received a message from my friend Sheena Page with details of this eighteenth century estate for sale in Cornwall. Incredibly, it was near where I had placed Sir Anthony’ house but even more incredibly, it fitted the bill exactly.

This is how the estate agent, Johnathan Cunliffe described the house. The once magnificent gardens and pleasure grounds at Pengreep, which now await an avid gardener to re-tame the present ‘wild abandon’, include a two-acre walled kitchen garden with the remains of a series of heated greenhouses and a series of four stream-fed ponds — some two acres of water in all — that not only provide a romantic setting for the house, but contain naturally stocked brown trout and are a haven for herons, kingfishers, wild mallard, geese and other wildfowl.

An extraordinary coincidence, and another spine tingling research moment.

Trenwyn House

The Carew’s fictional house, Trenwyn House, is based on National Trust Trelissick House. In 1801 the house did not have the beautiful columns it has now but was like the above early print. I have, however, taken the liberty of adding a landing jetty so my characters don’t have to scramble over the rocks.

Mandrake.

I’m afraid I can’t attribute this photograph of mandrake, found on a Cornish beach, to anyone. If this is your photo, please get in touch. Several years ago, I saw this photograph on Instagram and took a screen shot, without knowing I would use it in any of my books. Or maybe I did know? Maybe I knew, one day, I would have to use it in a story. They do look like parsnips, don’t they?