A Cornish Betrothal

Cornwall, 1798.

Eighteen months have passed since Midshipman Edmund Melville was declared missing, presumed dead, and Amelia Carew has mended her heart and fallen in love with a young physician, Luke Bohenna. But, on her twenty-fifth birthday, Amelia suddenly receives a letter from Edmund announcing his imminent return. In a state of shock, devastated that she now loves Luke so passionately, she is torn between the two.

When Edmund returns, it is clear that his time away has changed him – he wears scars both mental and physical. Amelia, however, is determined to nurse him back to health and honour his heroic actions in the Navy by renouncing Luke.

But soon, Amelia begins to question what really happened to Edmund while he was missing. As the threads of truth slip through her fingers, she doesn’t know who to turn to: Edmund, or Luke?

Foyles

Hive

Rakuten Kobo

Amazon

Waterstones

Barnes & Noble®

WHSmith

Australia: New Zealand: US

Member of the Historical Writers Association and the Romantic Novelist Association

Since hearing of her fiancé’s death, Amelia Carew has thrown herself into creating a physic garden in his memory. Her physic garden supplies physicians and apothecaries all over Cornwall and her reputation as a herbalist is growing. She is on the committee for the new infirmary and her life has taken on new meaning now she has fallen deeply in love with a young physician, Luke Bohenna.

Reeling with shock that Edmund Melville may still be alive, and consumed by guilt that she’s allowed herself to love again, Amelia re-reads Edmund’ letters, reliving the exuberance of their youthful courtship, their vows, and his growing concern for his father’s failing spice trade. Everything they planned together comes flooding back and she knows she cannot desert the man who has always adored her, who has fought valiantly for his country, and has suffered so much in the line of duty.

“The day was overcast, a thick blanket of clouds sitting heavily above the town. Men stood hunched against the biting wind, the corner of High Cross almost deserted. Luke was right on time, dressed in his heavy overcoat, his collar pulled up, his hat drawn low over his ears, and I thought my heart would burst. He was smiling up at me, that loving smile that made my whole body flood with warmth.

‘Yer mother’s foot’s done very well under Dr Bohenna’s attentive care. His daily visits have made all the difference.’ Bethany was as flushed as I was and well she might be, all of them thinking I had fallen for their ruse. ‘I do believe Lady Clarissa will soon be up and able to walk on her broken ankle.’

Luke had not yet knocked on the door and stood smiling up at my window. I leaned against the pane and smiled back. ‘I take it Papa has had no more of those dizzy turns?’

‘None that I know of . . .’

‘And Cook’s headaches have stopped . . . and Seth’s indigestion is better?’

Bethany had the grace to giggle. ‘All better. All thanks to Dr Bohenna.’

The footman must have opened the door because Luke picked up his heavy leather case and disappeared under the pillared portico. Across the square, the stones of St Mary’s church were growing increasingly grey, the spire now swallowed by the darkening sky…..” (Page 6)

“ Snow was building against the leaded windows, the room in half-darkness. Edmund was sitting at the large desk surrounded by a mound of papers. He had his back to me, and my heart jolted in sudden fear. His familiar long black curls were cut short, a pair of broad shoulders filling every inch of a well-tailored jacket. He was holding a letter to the candlelight, bringing it nearer and further from his eyes as if having difficulty reading it, and I tried to calm my growing panic.

It looked like a stranger’s back. A stranger’s shoulders. A stranger’s hand reaching for a magnifier. I could not enter but stood silently watching. Glass-fronted bookcases lined the walls, heavy oak furniture where it had stood for hundreds of years. Two high-back chairs sat either side of the fireplace, two knights in armour defending the Melville family crest. Firelight flickered across the ornate plasterwork, portraits of long-deceased relatives looking out from their heavy gold frames.

The stranger ran his hand through his hair and sudden fire burned my heart. The sweep of his hand, the slight toss to his head; if I was right, he would put down the letter and hold his hands against his lips as if in prayer. He would tap his fingers three times, then rest his chin on his interlocked hands. I had watched him do that too many times to count – smiling up at me through his wave of black curls.

One tap. Two taps. Three taps, his chin rested on his interlocked hands and the years stripped away. I stepped forward…” (Page 150)

“We were pointing east, the grey streaks of dawn turning pink, lighting the sky ahead. The stars were fading, the moonlight less intense. A faint shadow of land rose to our left and James pointed to some lights just visible through the swell. ‘That’s the entrance to Polperro harbour – we’re making excellent progress. I’ll get us some blankets. The moment you feel too cold, you’re to go below. I’ll not have anyone on my ship incapacitated from cold.’

For the effective cure of motion sickness, whether it be in a carriage or on the sea: add a full half-teaspoon of freshly grated ginger, or two teaspoons of dry-powdered ginger, to a cup of newly boiled water. Add a pinch of sugar to taste and the top two leaves of a fresh sprig of peppermint. Leave to infuse, then strain through muslin and drink whilst warm. The chewing of raw ginger, though efficacious to some, is found unpleasant by most and therefore not to be recommended.“

The Lady Herbalist (Page 336)

The inspiration behind A Cornish Betrothal.

The setting of Pendowrick is based on Trerice in Cornwall.

The ancient manor house, Trerice, has long been one of my favourite National Trust properties. Set in a peaceful wooded valley with Dutch gables and tall chimneys, it has the exact atmosphere I wanted to capture in my novel – a house full of secrets, with a minstrel gallery where conversations are overheard, and long corridors leading to cold, draughty rooms. But when I saw the steep, spiralling stone steps used by the servants my story came to life.

I could see snow beginning to fall, the house cut off in a terrible blizzard.

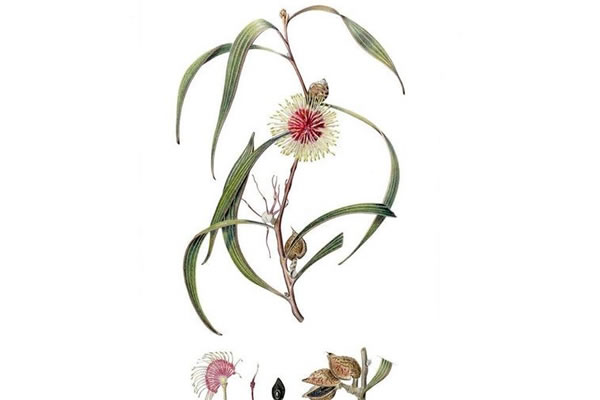

The Royal Cornwall Infirmary, Truro.

In my book, Amelia is on the Infirmary Committee and is charged with designing and supplying the physic garden for the new hospital.

The place chosen for the Royal Cornwall Infirmary was on higher ground above the main streets of Truro to obtain cleaner air and avoid contamination from the town’s sewers. Completed in May 1799, it was designed by William Wood who was also the architect of the Lemon Street development in the town. In June 1799, a matron, porter, and other members of staff were elected and the first patients arrived on August 12th.

The infirmary was funded by subscription and opened with 20 beds, 10 for men and 10 for women, with the two wards on separate floors. In the first year, a total of 47 patients were admitted.

Three years previously, in 1796, Edward Jenner had discovered the first effective vaccine against smallpox and soon after it opened the doctors in the infirmary started a campaign to promote the vaccine. At the time, smallpox caused one death in twelve and those who survived had a 25% chance of suffering blindness.

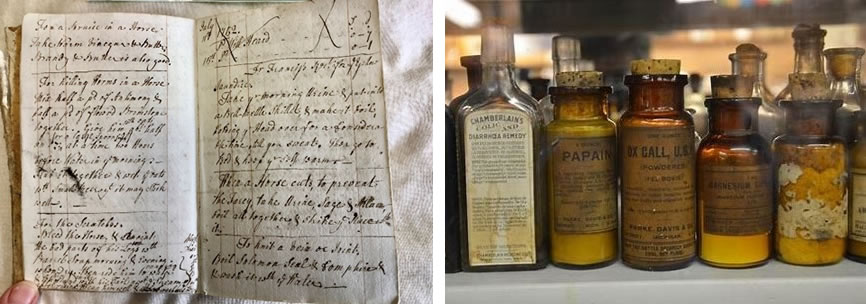

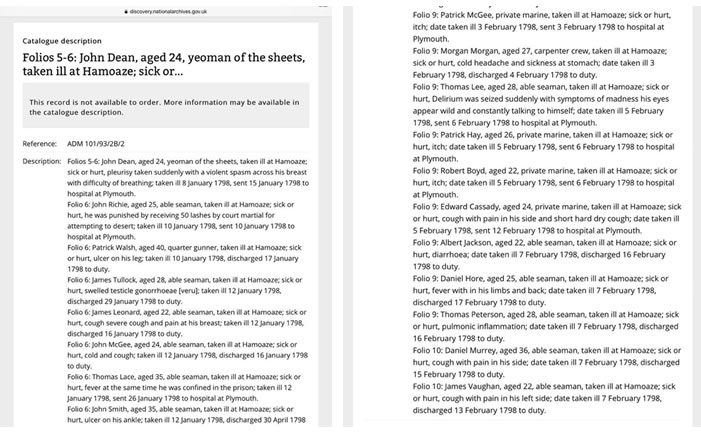

My trusted and extremely helpful assistant (well, my long suffering husband) and I had a fascinating day researching the Cornwall Record office for 1790’s medical records – although it is now housed in Kresen Kernow in Redruth. They hold a fascinating selection of apothecaries’ remedies and doctors’ bills, as well as records of the meetings held by the new Infirmary Committee. I’d like to thank everyone in the Archives and Cornish Studies Service for their unwavering enthusiasm and help, and I acknowledge them as custodians of these original documents which are still subject to copyright. These are my photographs of two of the records we found – R/4754 and HL/2/219

Miasma – sometimes known as night air – is a noxious vapour that caused disease.

The miasma theory, also known as the miasmatic theory, concluded that noxious exhalations from putrescent organic matter, once inhaled, could lead to cholera, chlamydia, yellow fever, undulating fever, the plague, and just about every unremitting fever.

While germ theory was still some way in the future, and no-one thought to link mosquitoes to any of the diseases, a number of doctors in the late eighteenth century began questioning the miasmatic theory. While they believed diseases to be the result of contaminated water, foul air, and unhygienic conditions – as identified by foul smells – they began to question whether it might be possible for diseases to pass from person to person rather than only be caught in the locality of the bad smells and putrid drains.

The debates of contagionists versus anti-contagionists continued well into the mid 1800’s when Louis Pasteur, John Snow and Robert Koch took up the baton but it wasn’t until 1897 that Ronald Ross discovered the link between mosquitoes and malaria.

Quacks and horse doctors

By the end of the eighteenth century, quacks, or quackery, was a profoundly serious problem. Degrees in medicine could be bought and many patients were often duped into using the poisonous concoctions made by unscrupulous practitioners rather than the medicines advocated by trained physicians, surgeons, or apothecaries. Unregulated practitioners like Dr Solomon of Liverpool who made his fortune making and selling Cordial Balm of Gilea, and Dr Spilsbury who made Antiscorbutic Drops or Dr Daffy’s cure all Elixir might just have readily used mercury as they did Senna leaves.

Fortunately an Irish-born writer, John Corry, not a medical man, took it upon himself to expose the fraudulent practices making some of these men very rich. In 1802 he published The Detector of Quackery which went some way to rouse the public’s indignation as well as warning them of the dangers of these innocuous looking lozenges and pills.

Below is a horse doctor’s notebook we found among the archives in the Cornwell Record office. It remains under copyright with the Archives and Cornish Studies Service as custodian of the original document.

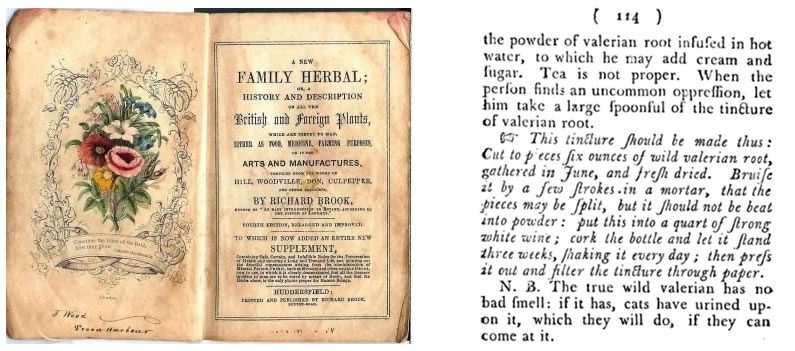

Herbals and botanical prints

In 1798 my aristocratic character, Amelia Carew, wouldn’t be allowed to study botany at university as did her brother, but she would have had access to public lectures and illustrated books of plants. She certainly would have had access to a microscope, and she would have known all the Latin names. She would also have kept up to date with the changing classification of plants. I’ve taken the liberty of allowing my character the honour of having her prints published by a renowned publisher, but many young women in her position might have had their prints published through subscription.

The recipes and herbal extracts of my fictious The Lady Herbalist are compiled from content found in primary sources, information taken from Culpepper’s Complete Herbal, Primitive Physic, and An Easy and Natural Method by John Wesley, as well as various on-line herbal remedies as advertised today.

French prisoners on parole in Bodmin

By 1798 it was estimated that the cost to Britain for keeping over 11,000 French prisoners was upward of £300,000. Very few prisoner exchanges took place, with rumours circulating that France wanted Britain to bear the entire cost of the prisoners as it would weaken the economy and force Britain to make peace.

Lower ranks were held in prisons like Norman Cross but officers were permitted to live in designated parole towns like Bodmin. In exchange for giving their word not to escape, officers were granted the freedom to live in lodgings under certain strict conditions.

They were required to live in, or near, one of the parole towns, limit their walks to one mile along the turnpike road from the boundary of the town, and be in their lodgings during the hours of darkness. Twice weekly, they had to report to the local Agent of the Transport Board.

The agent was responsible for the regular muster and for paying each prisoner his subsistence allowance which increased in 1809 to Is 6d a day for second lieutenants and naval aspirants; Is 3d for officers of merchant ships and Is each for wives and children.

Householders who received parole prisoners were given a printed reminder of the terms of the parole and had to ensure their prisoner obeyed the curfew by remaining indoors between the evening and morning bells.

There were many complaints from parole prisoners that their allowance was inadequate. They had to pay for their room, sometimes provide furniture and they had to pay for their food, so it is hardly surprising they put their skills to good use.

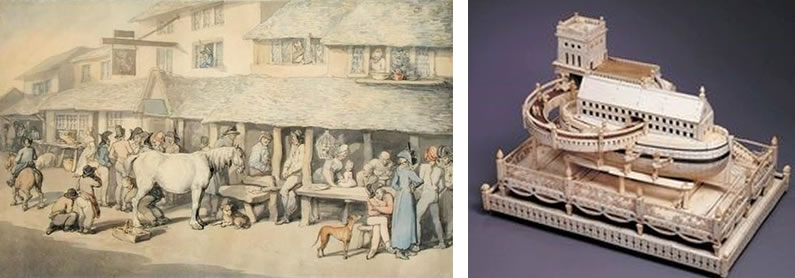

They organised regular markets, as illustrated in Thomas Rowlandson’s painting below called Bodmin 1795: French Prisoners on Parole and sold exquisite articles they had made – like paper sculptures, straw marquetry, often straw hats. Using bones from their meat rations, they carved animals and decorated boxes, making screens and other wooden objects – like models of ships, cannon, guillotines, musical instruments, and Noah’s Arks.

With their freedom of movement, the officers often gave lessons in French, drawing or fencing.

My fictional character, Captain Pierre de la Croix, is based on one of two hundred parole prisoners present in Bodmin in 1798.

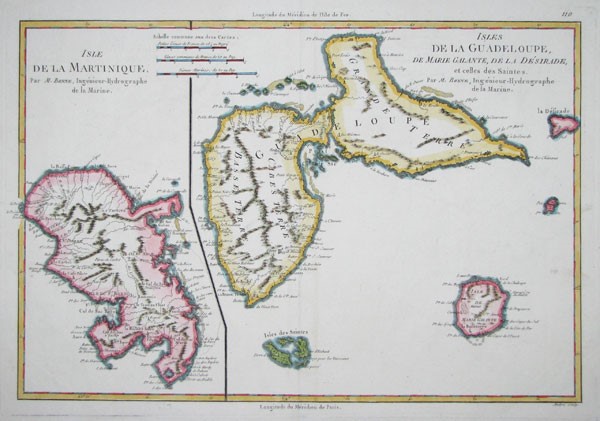

Guadeloupe in the West Indies: 1793-1798

Guadeloupe was a French colony, but after the French Revolution, there was bitter conflict between the long-established French monarchists on Guadeloupe and those now faithful to the new Republic. Despite the growing opposition from the Republicans, the Royalist landowners, planters, and merchants were a powerful force and they kept firm control of the small island.

However, when the new French Constitutional Assembly passed a law freeing all slaves, a slave rebellion broke out among the plantations in the Caribbean islands and the Royalist landowners on Guadeloupe knew the only way they could keep their slaves enslaved would be to seek assistance from Britain.

Under the leadership of Ignace-Joseph-Philippe de Perpignan and Louis de Curt, these plantation owners sought British protection and asked Britain to occupy their island which Britain readily agreed to do.

The Whitehall Accord was signed in February 1794 and a fleet led by Admiral Sir John Jervis, together with troops commanded by General Charles Grey, landed on Guadeloupe in April. They accepted the surrender of the last stronghold at Basse-Terre from General Collot and brought Guadeloupe under British control. They were, of course, supported by the French Royalists landowners who continued to use slave labour in their plantations.

Conditions were harsh and yellow fever, among other tropical diseases, took a huge toll on the British garrison left holding the island. Weakened in strength and numbers, they continued to encounter pockets of resistance from the French nationals loyal to the new Republic.

British hold on the island was not to last long. Barely six weeks later, On 4 June a French fleet under the command of Victor Hughes, successfully gained a footing on the island and by the end of the year his troops had forced the British to evacuate. Victor Hughes then set about freeing the slaves, imprisoning and guillotining the Royalists landowners who had sided with the British.

Despite growing support for the abolition of slavery by the Quakers and Abolitionists, among them The Clapham Set and the leading voice of William Wilberforce, it remains a sad fact that the buying and selling of slaves was only made illegal across the British Empire in 1807, and owning slaves was permitted until it was outlawed completely in 1833.

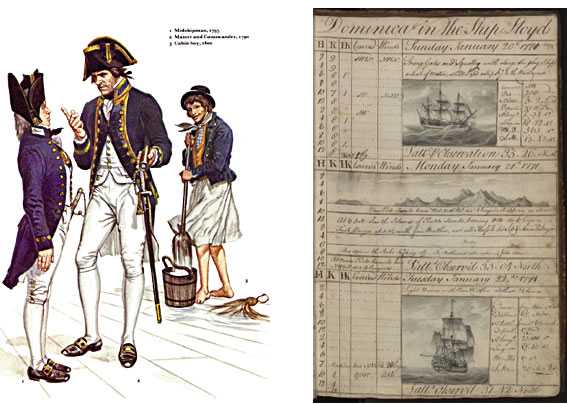

Duties of a Midshipman

I thoroughly recommend the thesis A Social History of Midshipmen and Quarterdeck Boys in the Royal Navy, 1761-1831, submitted by Samantha Cavell to the University of Exeter in February, 2010. It details everything you could possibly want to know about Midshipmen during the period of my book.

I also recommend Life in Nelson’s Navy by Dudley Pope, as another wonderful resource.

Just to recap …

- Midshipman is the lowest officer rank.

- A few midshipmen were aged 14, but most were 20-30 with some over 40.

- Midshipmen couldn’t be promoted until they passed an exam for Lieutenant.

- They could not sit for the exam until they produced certificates showing that their name had been on a ship’s book for 6 years – 2 of which had to be spent as midshipman or master’s mate. This 6 year time constraint led to many names being put on ships’ books long before the Midshipman actually went to sea.

- Their duties included keeping a daily log, calling the muster, piping commands, supervising the distribution of grog, and maintaining discipline among the Tars, as well as learning seamanship and navigation.

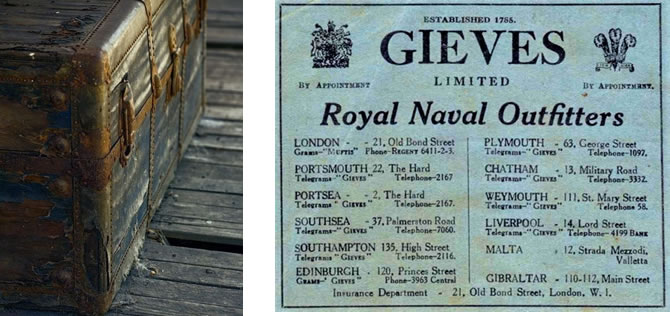

A Midshipman’s Chest

When an officer, like my character Midshipman Edmund Melville, died away from Britain, only his personal belongings were kept. Space on the ships was too tight to keep extra chests so their uniforms and non-personal possessions were sold and bought, sometimes very generously, by their colleagues. Money from the auction was then sent to his family.

This makes good sense as some of the sea chests were quite substantial. It also plays an important part in my story.

Below is an entry from Jarrett, British Naval Dress, pp. 46-47, which details a list a servant complied of the contents of Midshipman W. H. Webley’s sea chest. (Midshipman Webley was clearly destined for higher office as he later became Rear-Admiral W. H. Webley Parry, C.B.)

1 Frock (took along with him).

2 Jacket Suits (took one of ‘em along with him).

6 pr Trowsers (took two of ‘em along with him).

2 great coats (took one of them along with him).

14 plain shirts, 4 ruffled ditto (three of them he took with him).

6 pr of thread, 6 pr of worsted, 6 pr of cotton and 2 pr of silk. [stockings]

9 red handkerchiefs, 3 white ditto, 2 black silk stocks.

2 black silk neckcloths,

6 pr shoes.

A Quadrant. Robertsons Elements, papers and Pens, Seaman’s Daily

Assistant. Two pounds of powder,

2 pr Buckles (one of ‘em he took along with him).

1 pr of boots he took along with him

2 pr nankeen breeches, 1 pr corduroy, 2 waistcoats, 2 roundhats

1 Bible, 1 Prayer Book, 6 towels, one pr sheets. One table cloth, 3 caps,

two nets.

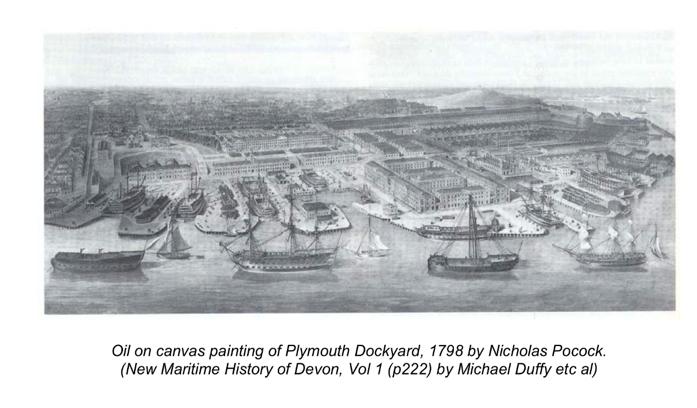

Plymouth Dock

With the war in full swing the navy needed a shipyard where it could not only build and repair ships, but also anchor and provision a whole fleet. By 1798, Plymouth Dock was a huge, bustling town catering for every aspect of the King’s Navy. It had four dry docks (the newest large enough to hold two ships at a time), four new slipways, and seven large storehouses.

The Rigging house was 480ft long, 3 stories high, with a sail loft on the top floor. The Ropehouse consisted of two long stone buildings running parallel where the ropes were twisted together to up to 23ins in diameter.

The blacksmiths’ shop had 48 forges, converting huge iron bars into enormous anchors worth £550 each. Large cranes lifted the dripping red bars in and out of the furnaces with chains cranking up the bellows to blow air onto the fires.

The masthouse had a large pond with seawater entering through sluices. The pond was 400ft long and kept dozens of masts and scores of yards from drying out.

The victualling office was near the citadel. Numerous coopers made thousands of barrels to store food and water and two bakehouses, with four ovens in each, cooked the ships’ bread which we now refer to as biscuits. Butchers slaughtered meat to salt and pack into barrels and great cauldrons bubbled with cabbage and onions to make sauerkraut. Other kitchens cooked vast quantities of stock which was dried and packed into caskets to be re-constituted onboard ship.

Not to mention the live chickens and pigs that were loaded onto the ships in crates and the barrels of fresh vegetables, beer, and brandy. Added to this were the taverns and hotels, the tailors, and the boatmen who ferried the sailors out to the ships from the Western Pier – 1s to the Cattewater, 3s to the Sound, 5s to Cawsand and Hamoaze.

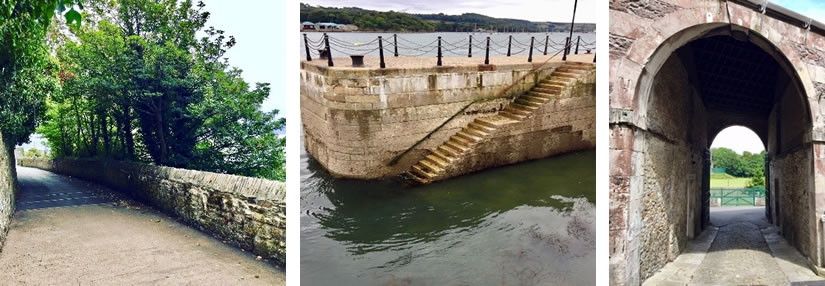

Here are a few photographs I took on the day we traced the footsteps of my characters in their dash to Plymouth Dock – Richmond Walk, Mutton Cove, and the slipway are still there, but Gieves the naval outfitter is no-longer at 63, George Street.

Stonehouse Hospital

Stonehouse Naval Hospital in Plymouth was built between 1758-1765 and was the first hospital built with separate ward blocks to minimise the spread of infection. The ward blocks were linked by a colonnade and until the operating theatre was built in 1790, surgery took place in the wards.

Sick sailors were rowed straight from their anchored ships to Stonehouse Creek to be admitted through a heavy iron gate at the end of a tunnel. This tunnel was part of the huge encircling walls that were built to prevent ‘pressed’ sailors from escaping.

The tunnel, gates, and encircling walls are exactly how it was in the time of my book, but the creek is now a playing field, and the exercise yard is a well maintained lawn as the hospital was sold in 1995 and converted into private apartments.

But take a close look at this! Here are the records of the sailors admitted to Stonehouse Hospital on February 6th 1798 – just before my character, Sir James Polcarrow visits the hospital.

Folio 9, Thomas Lee, Aged 28, able seaman, taken ill at Hamoaze: sick or hurt. Delirium was seized suddenly with symptoms of madness his eyes appear wild and constantly talking to himself …

And finally, miniature portraits.

I love miniature portraits and I’m thrilled to include one in my story.

The first portrait is a watercolour on ivory of Stephen Thorn by George Augustus Baker 1818

The second is also a watercolour on ivory miniature portrait of Captain Roger Curtis, R.N. painted by George Engleheart (1752 – 1829).

Acknowledgements

I loved writing this book, but part of what I enjoy most about writing is the people I meet and the discussions that follow. My thanks to the archivists in the Cornwall Record Office, now housed in the fabulous Kresen Kernow, for unearthing the infirmary records, doctors’ bills, and apothecary recipes which form the background to the book. My thanks as well to Dr Kenneth George, distinguished oceanographer, poet and linguist, for his advice about the integrity of Cornish place names. This is my fifth book and each time I feel honoured to have such a wonderful team behind me. My thanks to my agent Teresa Chris for her unstinting support and my editor Susannah Hamilton at Atlantic Books whose deft pen and sure hand has made this the book it is. Thank you also to Poppy Mostyn-Owen, Sophie Walker and Kate Straker, among so many, and to my copy-editor, Alison Tulett, for her eagle eyes. My thanks, as always, to my husband, Damian, and to you, cherished reader: thank you for your interest in my books.