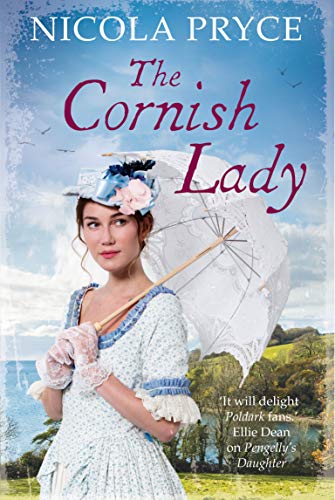

The Cornish Lady

Cornwall:1796

Educated, beautiful and the daughter of a prosperous merchant, Angelica Lilly has been invited to spend the summer in high society. Her father’s wealth is opening doors, and attracting marriage proposals, but Angelica still feels like an imposter among the aristocrats of Cornwall.

When her brother returns home, ill and under the influence of a dangerous man, Angelica’s loyalties are tested to the limit. Her one hope lies with coachman Henry Trevelyan, a softly spoken, educated man with kind eyes. But when Henry seemingly betrays Angelica, she has no one to turn to. Who is Henry, and what does he want? And can Angelica save her brother from a terrible plot that threatens to ruin her entire family?

Waterstones

Foyle

Barnes & Noble

Amazon

Rakuten Kobo

Hive

WHSmith

Australia: New Zealand: US

Member of the Historical Writers Association and the Romantic Novelist Association

Daughter of a renowned London actress and wealthy smelter, Angelica Lilly has been longing to visit the Carew’s country estate with its sweeping lawns and views over Carrick Roads and Falmouth. An advantageous marriage is on the cards which would not only raise her family’s status but would fulfil her beloved mother’s dying wish. Angelica has it all – fine clothes, a huge dowry, poise and elegance coupled with great beauty and charm and men are clamouring for her hand; only her insecurity is holding her back.

One scorched summer followed by two rain lashed harvests have brought food shortages to Cornwall. The wheat and corn fields lie in ruin and riots and disorder inevitably follow. Starving men watch food flow into the gaols crammed full of French prisoners. While Lord Carew surveys his fields with furrowed brow, Angelica stares anxiously at the turrets of Pendennis Castle, knowing her secret must remain hidden.

Yet one man knows the truth – the coachman, Henry Trevelyan. His keen eyes miss nothing.

"'I saw you run across the terrace and into the shrubbery so I can to see you safely back.’

‘I’m in no danger, thank you, Mr Trevelyan.’

‘What about the danger of enchantment, Miss Lilly? Puck might be watching, Oberon and Titania fighting over you this very minute – the interference of woodland sprites can cause great mischief.’

I wrestled his joyous laughter from my mind, his sunburned arms, Freddie on his shoulders as he bowled to William. ‘No danger of enchantment,’ I replied firmly.'" Page 76

“You who are so fearless. The gingerbread pig lay flung in the waste bin, the pain of Henry Trevelyan’s betrayal still cutting like a knife. I had been too free with him, both times completely myself: no mask, no biting back my words, the real Angelica Lilly standing so defiantly, the horses’ hooves thundering beneath her. Laughing at the danger, flinging away the key; the real Angelica slipping from the house by moonlight, glancing up at the ladders she knew would take her back to her room.

I had exposed myself so completely. Well, let him know the real me, let him take heed. Let him understand just how fearless I would be in my brother’s defence.” Page 204.

“Our pass duly studied, the new guards opened the door to a dimly lit corridor with worn flagstones and smooth granite walls, the air so rancid it was barely breathable. The musty dampness stung my nostrils, the fat from the candles making me want tor retch. Two shut doors led from the right, two more rush lights burning against the wall, and I caught my breath, my fear doubling. Light permeated the darkness at the end of the corridor and we walked slowly towards it, the corridor ending in a large room with a huge stone fireplace and an arched brick ceiling. Light was filtering through a small mullion window, the panes dirty, smotthered with cobwebs, and I caught the outline of a carved Tudor rose.

‘We have to get him out of here,’ I whispered as Mary held her handkerchief against her nose.” Page 184

The inspiration behind the book’s setting and my characters

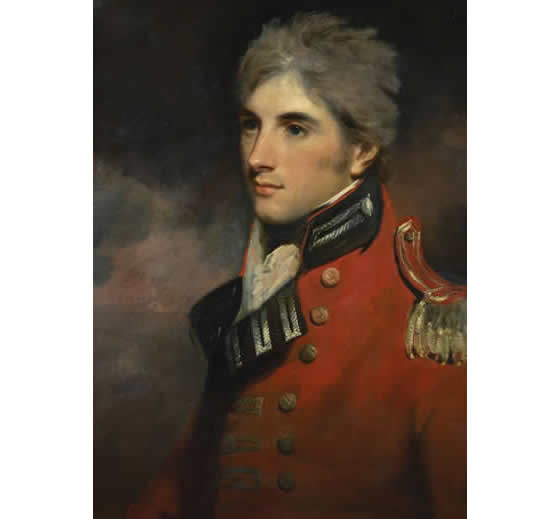

Pendennis Castle stands on a jagged promontory guarding the harbour of Falmouth. At the time of my book Felix Buckley was the absentee Governor and the castle was woefully manned by a Company of Invalids, numbering no more than about 40. The fortifications were in a semi-derelict state and the Invalids were under the charge of an acting Captain who complained the Company were drunk and disorderly and barely obeyed commands. Phillip Melvill was about to take up his appointment as Lieutenant-Governor which he did until 1811.

These photographs of the Tudor kitchens in Pendennis Castle kick-started my story. They're taken from the website cornwalllive.com and show the Tudor basement of Pendennis Castle (which is not open to the public) where French prisoners were briefly held before being transferred to Norman Cross. In her article, Jade Bone, property supervisor, says … Lifting the latch in the floorboards of the little kitchen are a set of precarious stairs leading to an enclosed basement which was used as a prison during the Napoleonic War and Civil War of Independence…

Once I'd seen these photos, I opened my laptop and started writing.

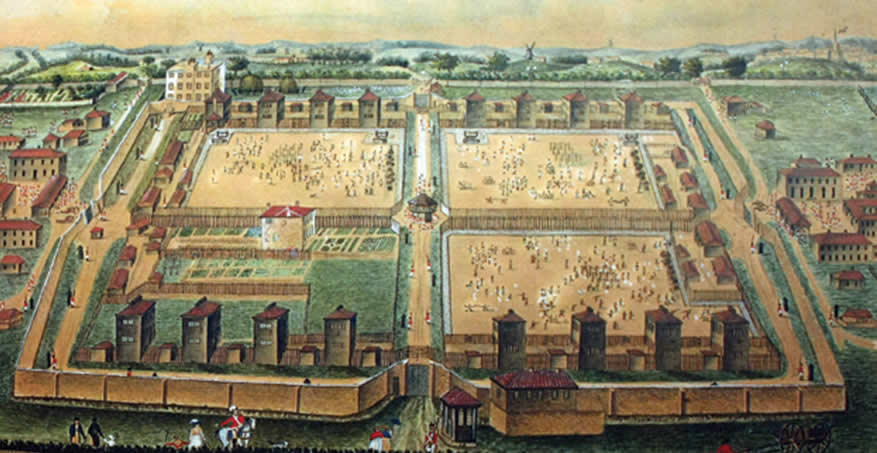

Norman Cross Prison. In my book, Admiral Sir Alexander Pendarvis is a memeber of the Royal Navy Transport Board’s advisory committee to build the new prison in Norman Cross. This was the world’s first purpose-built prisoner-of-war camp built during the Napoleonic Wars. The site chosen was on the Great North Road only 76 miles (122 km) from London because it was deemed far enough from the coast to deter escaped prisoners to flee back to France. The good water supply and access to food was important to sustain the many thousands of prisoners (upwards of 7000) and the guards. Work started in December 1796 with 500 carpenters and labourers working on the site for 3 months. It cost £34,581 11s 3d and was the first of its kind in the country, specially designed with health and hygiene in mind.

Lady Botanists and Herbalists

Elizabeth Blackwell (1707-1758)

A number of women, not just from aristocratic families, were active botanical artists during the eighteenth century. They read and wrote botanical books and went to lectures about botany. They corresponded with naturalists, collected and drew plants, developed herbaria, and used microscopes to examine plants, often working alongside their husbands and fathers interested in these pursuits. One such lady was Elizabeth Blackwell (nee Blachrie).

Elizabeth Blackwell (1707-1758) was among the first women to achieve fame as a botanical illustrator. Her project was a book called A Curious Herbal which she undertook to raise money to pay her husband’s debts and release him from debtors’ prison. She learned that physicians lacked a reference book which not only documented the medicinal qualities of plants and herbs, but also included illustrations to enable them to identify the plants, so she set about producing exquisite botanical engravings which she hand coloured. Prior to her Herbal no such herbal existed in England. Her choice of illustrations for the Herbal were based mainly on plants available in the Chelsea Physic Garden.

Other famous lady botanists worth looking up are Margaret Bentinck, Duchess of Portland (1715–1785) and Henrietta Maria Moriarty (1781-1842)

Plant Collectors

The job of a plant collector was fraught with both difficulty and danger and the safe transportation of seeds and live plants a constant challenge. There are too many to mention by name, but I believe John Ellis (1710-1776) was among the most successful plant transporters in the eighteenth century, although the most famous, perhaps, is Joseph Banks (1743 –1820) who accompanied James Cook on his voyages on the Endeavor.

The extreme temperatures, the salty air, the damp, the mildew, the long passages between ports were a constant battle and a number of ingenious methods were designed to protect the specimens, including various boxes with glass domes.

In my book, I mention the Scottish botanist John Fraser (1750 – 1811). In 1795 Fraser made his first visit to Saint Petersburg where he sold a choice collection of plants to the Empress Catherine. In 1796, he bought some Black and White Tartarian cherries back which he introduced into Britain for the first time.

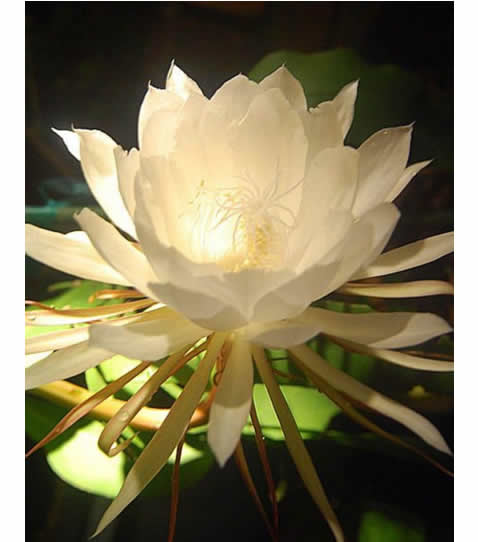

Back at home, the passion for exotic plants was growing apace. Huge purpose built hothouses with elaborate heating systems to enable safe cultivation were built to accommodate orchids and exotic plants like the Night Blooming Cereus. Pineapples became a symbol of prosperity and are often found on finials in eighteenth century gardens, or on the gateposts of grand houses as a symbol of their wealth.

Joseph Emidy and Captain Sir Edward Pellew

When I found the painting of HMS Indefatigable anchored in Falmouth in 1796, I decided to include Mr Joseph Emidy in my story. He was on the ship at the time and I took the liberty of having him alight in Falmouth, though I believe he was never allowed off the ship.

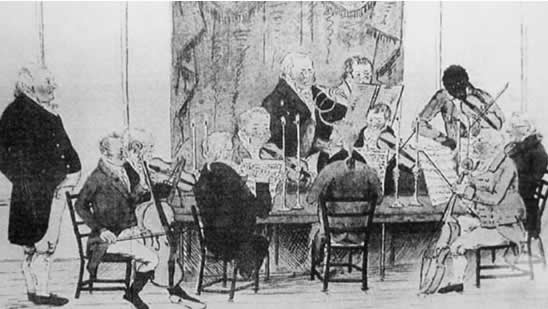

Joseph Antonio Emidy (1775 – 835) was eventually discharged from the ship in Falmouth in 1799 where he went on to earn his living as a violinist and teacher, eventually becoming the leader of the Truro Philharmonic Orchestra. He went on to become one of the most celebrated and influential musical figures in early 19th-century Cornwall, composing many works, including concertos and a symphony, although no copies are known to survive. In 1802, seven years after the date of my book, he married Jane Hutchins, a local tradesman’s daughter, and they had eight children. They moved to Truro around 1815.

Truro Theatre

In 1796 the assembly rooms were the centre of social life in Truro. They were built in 1780, in High Cross, and hosted grand balls and concerts. But what was very special about the building was the unique way part of the floor could be taken up to provide an orchestra pit and a well-defined stage for the performance of plays.

The facade of the building is still standing with its handsome Wedgewood plaques representing the Muse, Thalia, William Shakespeare and David Garrick but the interior has been lost. There are photographs of the interior at the Cornwall Museum in Truro, as well as the original painted frieze.

I mention this frieze in my book. Theatre troupes, such as the Thoedore Gillmore’s travelled from theatre to theatre putting on their plays.

‘Ah, cricket!’

Well, what’s not to love about divine men playing cricket! But did you know women also played the game, and really rather well as this painting of a cricket match played in 1779 by the Countess of Derby and other ladies shows?

The first county match was held in 1811 between Surrey and Hampshire at Ball's Pond in Middlesex.

The Large Black, also known as the Cornish Black, is Britain’s only all black pig. It’s a West Country breed which is thought to have originated when a ship carrying black pigs from China docked in Cornwall in the late eighteenth century. They were bred with the Old English Hogs of the 16th and 17th centuries and were reputed to be the perfect ‘cottage pig’.

Finally, the views that inspired the story: National Trust property Trelissick House

My husband and I are keen sailors and one of our favourite anchorages is the small bay below the gardens of the National Trust property Trelissick House on the Truro River. We were anchored here when the story of The Cornish Lady came to me. Just one glimpse through the window of the house and I could picture Angelica Lilly staring across the water to Falmouth and the outline of Pendennis Castle.