The Cornish Captive

Cornwall, 1800.

Imprisoned on false pretences, Madeleine Pelligrew, former mistress of Pendenning Hall, has spent the last 14 years shuttled between increasingly destitute and decrepit mad houses. When a strange man appears out of the blue to release her, she can’t quite believe that her freedom comes without a price. Hiding her identity, Madeleine determines to discover the truth about what happened all those years ago.

Unsure who to trust and alone in the world, Madeleine strikes a tentative friendship with a French prisoner on parole, Captain Pierre de la Croix. But as she learns more about the reasons behind her imprisonment, and about those who schemed to hide her away for so long, she starts to wonder if Pierre is in fact the man he says he is. As Madeleine’s past collides with her present, can she find the strength to follow her heart, no matter the personal cost.

WH Smith

Amazon

Waterstones

Blackwells

Rakuten Kobo

Barnes and Noble

Australia: New Zealand: US

Member of the Historical Writers Association and the Romantic Novelist Association

Silenced for fourteen years under a string of false names, Madeleine Pelligrew has struggled to maintain her sanity. Malnutrition and isolation have taken their toll, and her powers of reasoning are slipping. Marking each day with a scratch on the wall she constantly repeats her name and those in her family: she is not a French servant, but the wife of an English gentleman. Remembering the flowers she had planted in their herbaceous border may help her keep her grip on sanity, but far more powerful is her burning hatred of Sir Charles Cavendish. That alone is what has kept her lucid.

Convinced he was behind her husband’s death, she is determined to seek redress – Sir Charles Cavendish must be brought to justice. As her gallant rescuer urges the cart across Bodmin Moor there is only one thought in her mind. She must return to Pendenning Hall.

“ The crow of the cockerel. By his call, I knew him to be very large, his comb full-blooded and red, wobbling as he stretches out his long neck. He would have a fine plume of glossy tail feathers and a puffed-up chest. He must be perching on the branch, just out of sight.

Half-an-inch gap was more than ever before – a whole slice of the outside world: the straw-strewn backyard, the grey stones of the granite barn opposite. Pressing my eye against the gap, I could see a gate, and a pool of slops glistening in the moonlight. When the sun struck the pool, it turned murky grey. North facing because shadows soon fell across the yard. By midday the light dimmed. There he went again, so proud to herald the dawn.

You didn’t wake me, my friend. The terrible itching did.

Half-an-inch’s glimpse on the world was so much better than total darkness, far preferable to a cellar or an attic. Cellars bring rats, attics bring bats. Filthy farm outhouses may bring mice and lice, but at least I had Chanticleer.

Of course he’s called Chanticleer, dearest husband! Remember the cockerels in Clos-Poulet? Yes, of course you do.

The nail had lost its sharp point but it worked well enough. Another small line added to the others – every day accounted for; every seventh day a line through the others, every fourth week a ring around it. Every twelfth month, an underscore. One year and forty weeks. In twelve weeks’ time, they would move me again.” Page 15.

“ The golden-haired girl on his back was directing him, telling him which way to turn, the two boys darting towards him, running back, hoping to be caught, and I tried to quell the rush of pleasure seeing him had brought. Elowyn opened the small leaded window and leaned out.

‘That’s enough now!’ Her words were lost to screams of delight. The man reached forward, scooping up first one boy, then the other, tucking them both under his arms as he swung them round. Their squeals grew louder, his swirling getting faster, until the golden-haired angel on his back shouted for him to stop. She freed him of his blindfold and they stood laughing and gasping. Elowyn shook her head, once more leaning out of the window.

‘That’s quite enough! Leave poor Captain Pierre alone!’ She hid her smile. ‘The children adore him. He’d make such a lovely father.’

She poured our drinks and I took the glass, trying to hide my agitation. I wanted to leave, but there was more laughter, the sound of running footsteps, and I tried to stop my rising panic. He was at the door, dipping low to avoid bumping the child’s head on the lintel. His presence filled the room, a physical presence, and I fought the memory of his arm slipping round my waist.

A huge smile lit Mrs Pengelly’s face. ‘Ah, Captain de la Croix, we’re just having some refreshments. This is such a lucky coincidence. May I introduce Mrs Barnard, who’s lately arrived in Fosse?’ ”

Page 132

“ Never have I painted with more feeling, every stroke bringing him nearer. It was as if the linhay understood my heartache, as if the wind slowly lessened so that the flowers could stay still. As if the sun burst forth to highlight the vibrancy of the poppies, the pink blush of the foxgloves. As if the butterflies knew to linger, the beetles to stop halfway across the bricks. Everything conspiring to bring back the lonely man who had watched them with such reverence.

Our paintings drying, Rowan lay on the blanket, looking up at the skylarks. ‘I’ve never just lain an’ looked up at the sky. I can hear them but I don’t see them.’

I forced myself to glance upwards. No sudden rush of fear, no sense of being lifted, not pulled from the earth and whirled around. No giddiness. No terror. Just a beautiful blue sky and harmless white clouds. As if the linhay had understood that, too, and healed me.

‘We’ll paint the clouds next time,’ I whispered.” Page 355

The inspiration behind the setting and characters

Madhouses

Pendrissick Madhouse is entirely fictional, based on the unlicenced madhouses which proliferated under the 1775 Madhouses Act. These were ostensibly overseen by the Commission for Visiting Madhouses though many were never visited. The trade in lunatics was widespread and makes for difficult reading. My fictional Maddisons Madhouse is based on Mason’s Madhouse in Fishponds, Bristol, a pioneering hospital for the insane, which was established in 1738 and remained under the directorship of Dr Joseph Mason Cox during the time of my books.

That a vulnerable person could be locked away on the word of their guardian was undoubtably the case. Mania, they suggested, needed complete restraint and the strait waistcoat was frequently used. Confinement with few objects of sight and hearing was deemed vital, the patient removed far away from everyone he or she had formerly known.

Popular belief at the time was that lunatics needed to be kept in a state of awe or fear, cultivated by force which including beatings. Melancholics needed to be checked from the ramblings of imagination and protected from the incoherency of judgement. Cold baths, enclosed spaces, sleep deprivation, fetters and chains were a necessary cure.

But by the end of the 1790’s progress was slowly being made. A number of physicians, influenced by the famous physician William Battie (1703-1776), agreed with his A Treatise on Madness, published in 1758, and had taken up the baton, championing the belief that keeping an inmate naked, filthy, and chained with several others against the wall of a damp, dark stone cell was far from a cure. They echoed Battie’s claims that “bleeding, blisters, caustics, opium, cold baths and vomits” should be swopped for a more humane approach.

And we must not forget that at that time, George 111’s illness had brought the discussion of madness into sharp focus. He was treated at a madhouse in Shillingthorpe, Lincolnshire, which was run by Dr Francis Willis (1718-1807), just one of the 45 licensed premises at the end of the century. Most premisses, however, remained unlicenced with very little governance.

Favourite among my research is a painting I found of the innovative French physician, Philippe Pinel, called Releasing Lunatics from Their Chains at the Salpetriere Asylum in Paris in 1795 painted by Tony Robert-fleury.

It lead me to some further interesting research. In 1794 Pinel published his essay ‘Memoir on Madness’, where he called for more humanitarian asylum practices and made the case for careful psychological study of individuals over time. He stressed insanity wasn’t always continuous and could indeed pass.

His next publication in 1798, Nosographie philosophique ou méthode de l’analyse appliquée à la médecine led to him to be considered as one of the founders of modern psychiatry.

At the time of my book, discussions in Truro for a lunatic asylum were underway and I would like to think my characters Doctor Perrow and Madelaine Pelligrew would have volunteered to be on the committee. Certainly, they would have been careful observers when in 1815 the foundation stone for St Lawrence’s Lunatic Asylum was laid. Within three years, as part of the national program for building large institutional asylums, the hospital opened in Bodmin containing 112 cells with accommodation for 72 patients.

The Housekeeping Book of Susanna Whatman (1753-1814)

I had so much fun researching housekeeping in the late 1790’s, made even more enjoyable by the discovery of The Housekeeping Book of Susanna Whatman. Born in 1753, her book starts in 1776 when she marries James Whatman and finds herself in charge of a large house in Kent. If you are having difficulty recruiting or keeping servants this book is certainly for you! For over twenty years she records her detailed instructions, including when to draw down the blinds to stop the sun from fading the furnishings. My housekeeper in Pendenning Hall clearly had a copy of this wonderful resource – all of Mrs Pumphrey’s instructions come from this book. I bought my copy from the National Trust and I absolutely love it.

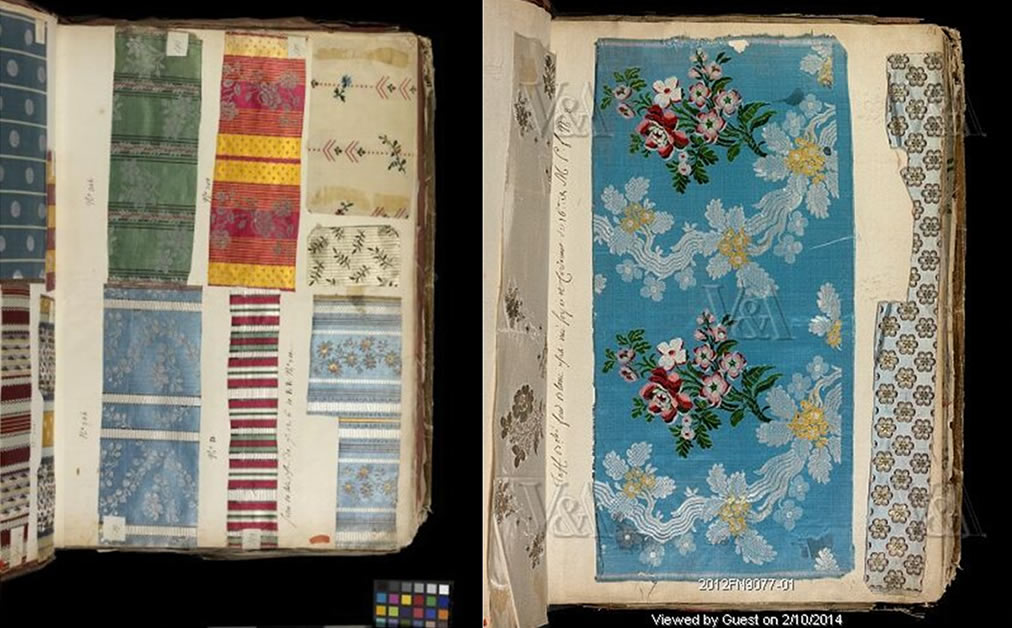

I needed an itinerant occupation for my character Thomas Pearce so I was delighted to find these silk swatch books housed in the V&A. A silk pedlar fitted my requirements exactly. Interestingly, I discovered that silk merchants in Bristol employed pedlars to roam as far as Cornwall in their quest to show their new designs to tailors and dressmakers. They would place all their orders through the pedlar.

What I wasn’t expecting to find was that the pedlars removed all the official labels from the sample books and rewrote their own labels so no-one seeing the silks would know which was which, so no-one could go behind their backs and order directly from the Bristol silk merchants. A very clever ploy to insure their commission!

Spying in 1800

The Copiale Cipher (above) was written in the late 18th century and shows just one of the many methods spies during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars used to get their messages through. Other ways were the use of invisible ink, musical ciphers, or mask letters which is where the central message would be read through a template – always sent separately. Spies would identify themselves through missing buttons or tears in their sleeves, the way they held their beer, or even the way they hung up their laundry.

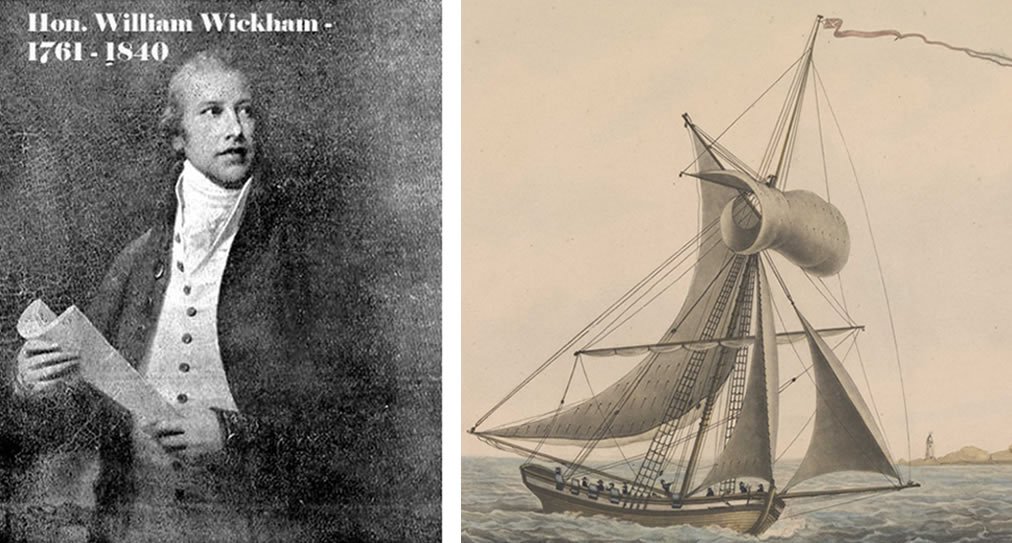

Researching spies during the French Revolutionary War left me almost no time to write, but as always, I’ve narrowed it down to where my books take place. The spy ring operating in my book is based on the Channel Island Correspondence – La Correspondance – a network run by Phillippe d’Auvergne from Jersey. His spies sent their information to William Wickham (1761-1840) who was the founder of the British foreign secret service.

One of Phillippe d’Auvergne’s men who commanded the Islands of Marcou on the eastern side of the Cherbourg peninsular was the British naval officer Lieutenant Price. I cannot be certain, but it’s interesting to note that Captain Charles Papps Price (1750-1812) was on active service on board HMS Badger in both the time and place where my book takes place.

Could you be married, yet not married?

The Marriage Act 1753 only recognised marriages in England and Wales which were performed by the Church of England in Church of England churches. Jews and Quaker marriages were also recognised but Roman Catholics and other Christian congregations had to be married according to the Anglican rites and ceremonies, even though they did not support them. Roman Catholic priests often recommended their parishioners marry in the Roman Church, then have their marriage legalised by a ceremony in their Anglican parish church. Otherwise, there was no redress if a husband deserted his wife, and visa-versa.

Certainly, the marriage in France between Madelaine and Joshua Pelligrew would have been deemed illegal if they had not re-married in the English local church.

The inspiration behind Pendenning Hall and Polcarrow

We first meet Pendenning Hall in The Captain’s Girl which is the main precursor of this book. It is based on Pencarrow House but I have moved my fictional Pendenning Hall to north of Porthruan. Over the years, a number of you have asked why I call my fictional towns Fosse and Porthruan in my books when they are so obviously based on Fowey and Polruan.

The answer is that I was a very new writer when I wrote Pengelly’s Daughter and my confidence wouldn’t allow me to use such hallowed names, but as I developed the series I realised I had to use proper place names to make sense of the stories – Truro, Falmouth, Bodmin.

But more importantly it’s politics. My hero, Sir James Polcarrow, is closely based on Sir Charles Rashleigh of the Greys party, whose family lived in Menabilly, not the Treffry family of the Blues party, whose family lived in Place House, Fowey.

Ahh …. Cherries en chemise!

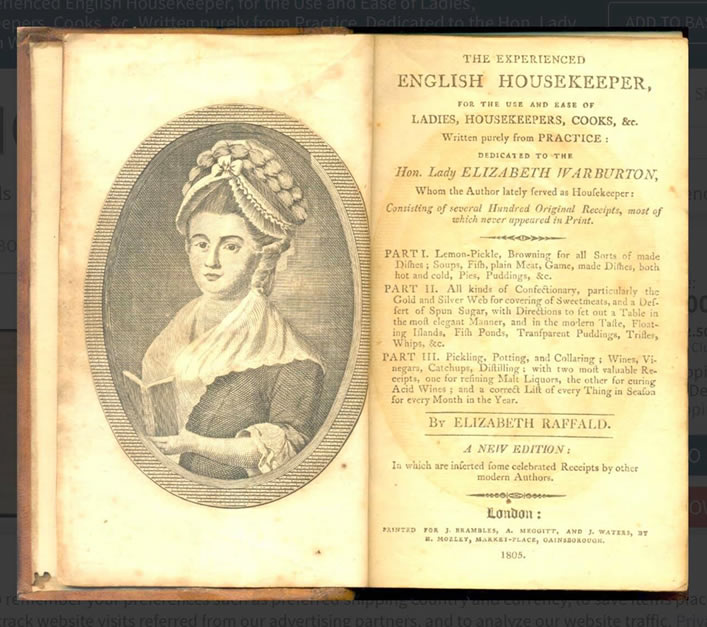

I can’t resist showing you the recipe that inspired Mrs Munroe’s cherries en chemise. Here’s the page from one of my favourite cookbooks – Tea with Jane Austen by Pen Vogler. Another resource I use when baking the recipes in my books is The Experienced English Housekeeper by Elizabeth Raffald 1733-1781, though I have to admit to having a revised version which makes the recipes much easier to read.