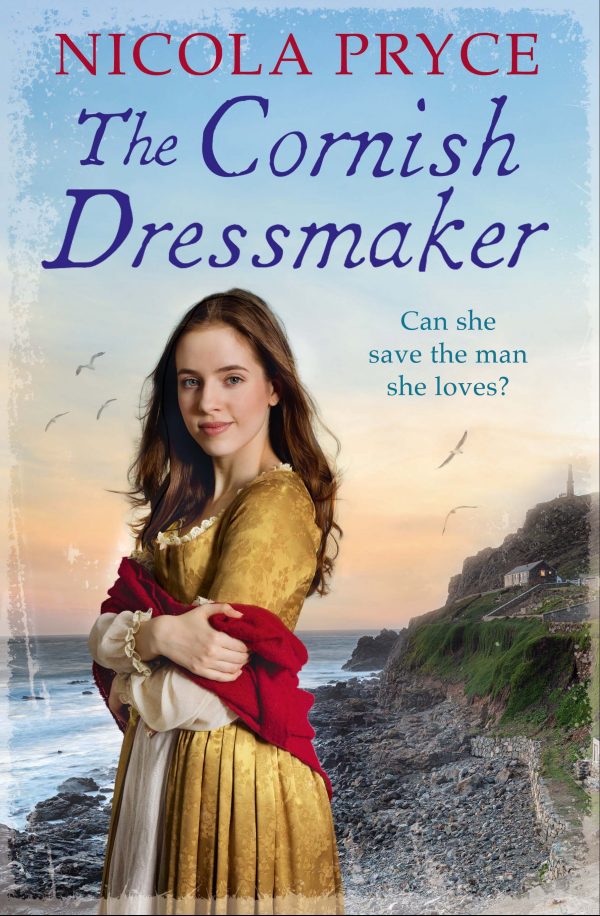

The Cornish Dressmaker

Cornwall, 1796.

Seamstress Elowyn Liddicot’s family believe they’ve secured the perfect future for her, in the arms of Nathan Cardew. But then one evening, Elowyn helps to rescue a dying man from the sea, and everything changes. William Cotterell, wild and self-assured, refuses to leave her thoughts or her side – but surely she can’t love someone so unlike herself?

With Elowyn’s dressmaking business suddenly under threat, her family’s pressure to marry Nathan increasing, and her heart decidedly at odds with her head, Elowyn doesn’t know who to trust any more. And when William uncovers a sinister conspiracy that affects her whole world, can Elowyn find the courage to support the people she loves in the face of all opposition?

Member of the Historical Writers Association and the Romantic Novelist Association

Sir James Polcarrow’s newly discovered china clay is beginning to show a profit. Investors are coming forward with a steady stream of agents arriving to ship it to the potteries in the midlands. Houses are under construction, indeed a whole new town is springing up around the ambitious new sea lock which enables ships to use every tide.

Behind the building and planning is Nathan Cardew, his ability only matched by his unswerving loyalty to Sir James. Hardworking and intelligent, rumour has it that he’s destined to become Piermaster.

The lease of Elowyn’s shop has run its course and her livelihood in under threat. Nathan Cardew is offering her so much. As piermaster’s wife, she would have everything she ever dreamed of – a loving husband, her own maid, her very own parlour.

So why can’t she rid her mind of William Cotterell? The man is a free thinker, a known risk taker. He’s proud and self-assured, and hated by her family. His dangerous thoughts are taking root in her mind.

She knows she should ask her uncle for advice but as her well-regulated world starts falling apart she does not know who to trust.

‘I rather liked his gentle teasing and smiled back, breathing in the scent of wild herbs. Skylarks were singing above us, swathes of wild flowers carpeting the fields. There was no river, just the gentle curve of the bay, the slope of the hill and one man’s determination to bring prosperity to his land. Ships were anchoring, the pilot gigs racing to be the first to reach the new ships entering the bay. This would be my new life – the bleating of sheep, the sound of cattle; the clatter of cartwheels down to the harbour. It was so beautiful, I wanted to stay where we were, sit down among the flowers and watch the ships.’ Page 58.

‘Will you not stop, Miss Liddicot?’ His voice held the same familiarity, the same disrespect.

‘How come you’re driving the cart? I sent the other man away.’

‘I was watching. I could see something was wrong and I can be very persuasive when I need be…’ From the corner of my eye, I saw him nudge Billy who laughed appreciatively. ‘Let’s just say, I managed to persuade the poor man that Mrs Hearne had sent me instead.’ Billy giggled even louder, clearly at ease with the man, sitting next to him like he had done it all his life. It felt like treachery, like being stabbed in the back.

‘You’ve stolen the cart?’

His laughter was deep, genuinely amused. ‘No, Miss Liddicot, I’ve borrowed it. I’ll take it straight back – Mrs Hearne may never know it’s missing.’ Page 75

‘I edged forward in the darkness, keeping close to the hedgerow. Waves were breaking against the rocks below, a steady rumble as the shingle rolled. I heard another hoot and caught my breath. The reply had come so quickly and I wanted to cry. Two men were up there. They were just ahead of me, walking to the track – one ahead of the other. I tried to stay calm. They were calling to each other, signalling their whereabouts, and I could judge their distance from their calls. One was quite close to me, maybe fifty yards, no more. I would wait and let them get ahead.’ Page 276

The inspiration behind my characters

China clay was first identified by the Quaker apothecary William Cookworthy in Tregonning Hill, in Cornwall in 1746. Living in Plymouth, he was just one of many searching for the illusive ingredient that enabled the Chinese to make such fine porcelain. Recognising the potential of the china stone quarried in the hills overlooking St Austell, he set about producing a hard-paste porcelain, finally succeeding in 1768 when he took out a patent and opened a pottery in Plymouth.

The early production of porcelain was fraught with difficulties and proved very expensive, forcing Cookworthy to close his Plymouth pottery in 1770. He set up again in Bristol but four years later retired, handing over his business to Richard Champion who tried, unsuccessfully, to extend the patent. By that time, the Staffordshire potters, led by Josiah Wedgewood were hard on his heels and keen to expand.

None of my characters is based on William Cookworthy, but he is crucial to the history of my story by playing a pivotal role in lighthouse engineering.

His associate, John Smeaton, was engaged in building the third Eddystone Lighthouse (1756–59) off Plymouth. Cookworthy helped Smeaton with the development of hydraulic lime . This, in turn, proved a crucial component in the building of locks such as Charlestown Lock, the setting to my story.

My fictional town of Porthcarrow, the construction of the outer harbour and inner lock, the use of leats, and the need to keep the water flowing, is based on the harbour of Charlestown near St Austell. In 1790 only nine fishermen lived in Polmear Cove with their families but by 1867 the population had risen to three thousand. The harbour and sea lock was built by a local entrepreneur Charles Rashleigh with the help of his Superintendent of Works, Mr Joseph Dingle.

![17 pompacornovgrande[1]](https://nicolapryce.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/17-pompacornovgrande1-e1506953863397.gif)

What fascinated me in my research was the mound of correspondence between Mr. James Watt, Mr. Matthew Boulton, Richard Trevithick and their lawyers. In 1796, Richard Trevithick was engaged in a patent row with James Watt who was successfully blocking any new engineers from using the technology behind his engines. It was a fierce legal battle, with James Watt regarding the young Trevithick as his chief enemy in Cornwall.

A long and very frustrating stalemate occurred with the price of coal rising steeply and the cost of copper and tin mining growing increasingly prohibitive. My story reflects the difficulties engineers faced during this strictly imposed patent.

![19 five-pound-note_2547217c[1]](https://nicolapryce.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/19-five-pound-note_2547217c1.jpg)

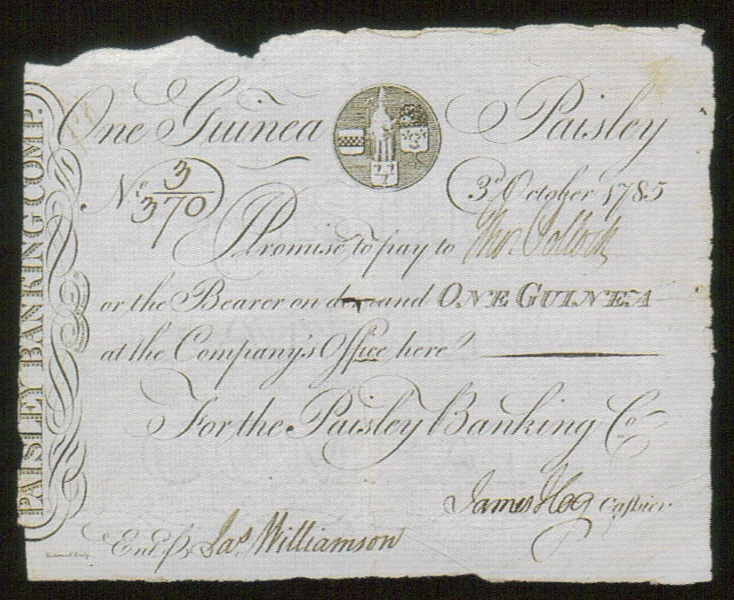

The coinage crisis had hit a new low. By the late eighteenth century there was an acute shortage of farthing, half penny, and penny denominations as no copper coins were issued. Small change was hard to come by which led to the practice of local manufacturers minting their own ‘tradesmen’s tokens’. These became accepted currency even by the banks.

In 1792 England was hit by a commercial crisis and with the declaration of war by the French in 1793 it became apparent that notes smaller than £10 were needed. Thus £5 notes were issued with local banks often issuing, and quarantining, their own notes of lower denominations such as £1 or even, one guinea.

When I discovered this my story began to take shape.

Even after the rise of Methodism huge profits were to be made from smuggling. War had disrupted trade and the preventative services were stretched and unsupported. Smuggling routes were well established, the harbours of south Cornwall but a hop away from France and Guernsey.